Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

Salvaged materials can be a cost-effective and environmentally friendly option for a variety of projects. Here’s a breakdown of what you need to know:

What are salvaged materials?

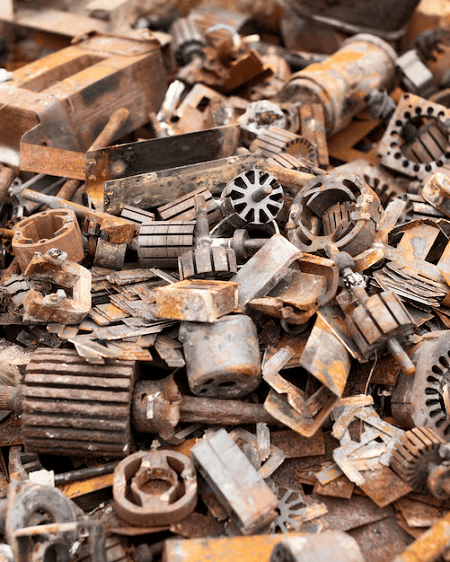

- These are materials that have been reclaimed from existing structures or products that are no longer in use.

- They can include anything from wood and brick to metal, doors, windows, and even plumbing fixtures.

Benefits of using salvaged materials:

- Cost Savings: Salvaged materials are often less expensive than new materials.

- Environmental Impact: Reusing materials reduces the need to extract new resources and helps divert waste from landfills.

- Unique Character: Salvaged materials can add a unique and vintage look to your project.

Things to consider when using salvaged materials:

- Availability: Finding the specific materials you need may take time and effort.

- Condition: Salvaged materials may require cleaning, repair, or refinishing.

- Quality: It’s important to inspect materials carefully to ensure they are structurally sound and suitable for your project.

Where to find salvaged materials:

- Demolition companies: Companies that specialize in demolishing buildings often salvage and sell materials.

- Architectural salvage yards: These businesses specialize in selling reclaimed building materials and architectural elements.

- Online marketplaces: Websites and online platforms can connect you with individuals or businesses selling salvaged materials.

Examples of salvaged materials in use:

- Reclaimed wood flooring: Adds warmth and character to a space.

- Antique doors and windows: Can be repurposed to create unique focal points.

- Vintage lighting fixtures: Bring a touch of history to your home.

If you’re considering using salvaged materials, it’s essential to do your research and plan accordingly. By carefully selecting and preparing salvaged materials, you can create a beautiful and sustainable project.

What is Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

Salvaged materials are materials that have been reclaimed from existing structures or products that are no longer in use. They can include anything from wood and brick to metal, doors, windows, and even plumbing fixtures.

Salvaged materials can be a cost-effective and environmentally friendly option for a variety of projects. They can add a unique and vintage look to your project, and they can also help to reduce the amount of waste that goes to landfills.

If you’re considering using salvaged materials, it’s important to do your research and plan accordingly. By carefully selecting and preparing salvaged materials, you can create a beautiful and sustainable project.

Who is required Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

Unfortunately, there’s no universal “Salvaged Materials 2.5%” requirement that applies to everyone. Here’s why:

- Regulations vary: Building codes and regulations regarding salvaged materials differ significantly between countries, states, and even local jurisdictions. There might be specific rules for certain types of projects or materials.

- Project-specific needs: The suitability and percentage of salvaged materials depend heavily on the project itself. A historical renovation might prioritize salvaged items, while a modern building might have stricter requirements for new materials.

- No standard percentage: There’s no common rule mandating a specific percentage of salvaged materials. Some green building certifications (like GGBC) might offer incentives or points for using them, but it’s not a mandatory 2.5% in most cases.

To find out if any specific requirements apply to your situation, you’ll need to:

- Check local building codes: Contact your local building department or consult the relevant codes for your area.

- Review project specifications: If you’re working on a construction project, the architectural plans or contract documents might outline specific requirements for salvaged materials.

- Research green building standards: If you’re aiming for a green building certification, explore the specific requirements and recommendations for salvaged materials.

Keep in mind that even without strict mandates, using salvaged materials can be beneficial for cost savings, environmental impact, and adding unique character to your project.

When is required Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

While there isn’t a universal “Salvaged Materials 2.5%” requirement, here’s when you might encounter specific regulations or incentives related to using salvaged materials:

1. Local Building Codes and Regulations:

- Historical districts: If you’re working on a building in a designated historical district, there might be regulations requiring the use of salvaged materials to maintain the area’s character.

- Specific project types: Some local codes might encourage or mandate the use of salvaged materials for certain types of construction, like public buildings or those receiving public funding.

2. Green Building Certifications:

- GGBC : Global green building council (GGBC) rating system offers points for using salvaged materials. While there’s no fixed percentage, using more salvaged materials can contribute to a higher LEED rating.

- Other certifications: Other green building certifications might have similar incentives or requirements for salvaged materials.

3. Project-Specific Requirements:

- Architectural plans: If you’re working with an architect or contractor, the project specifications might include requirements for using a certain percentage of salvaged materials.

- Client preferences: Some clients might specifically request the use of salvaged materials due to environmental concerns or aesthetic preferences.

4. Situational Considerations:

- Resource availability: In areas with limited access to new materials, using salvaged items might be necessary.

- Cost-effectiveness: When budgets are tight, salvaged materials can be a way to save money on construction costs.

Remember:

- Always check local building codes and regulations to ensure compliance.

- Even without strict mandates, using salvaged materials can be a sustainable and creative choice for your project.

COURTESY : The HISTORY® Channel Canada

Where is required Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

While there’s no universal “Salvaged Materials 2.5%” requirement, here’s where you might encounter specific regulations or incentives related to using salvaged materials:

1. Local Building Codes and Regulations:

- Historical districts: If you’re working on a building in a designated historical district, there might be regulations requiring the use of salvaged materials to maintain the area’s character.

- Specific project types: Some local codes might encourage or mandate the use of salvaged materials for certain types of construction, like public buildings or those receiving public funding.

2. Green Building Certifications:

- GGBC : Global green building council (GGBC) rating system offers points for using salvaged materials. While there’s no fixed percentage, using more salvaged materials can contribute to a higher GGBC rating.

- Other certifications: Other green building certifications might have similar incentives or requirements for salvaged materials.

3. Project-Specific Requirements:

- Architectural plans: If you’re working with an architect or contractor, the project specifications might include requirements for using a certain percentage of salvaged materials.

- Client preferences: Some clients might specifically request the use of salvaged materials due to environmental concerns or aesthetic preferences.

4. Situational Considerations:

- Resource availability: In areas with limited access to new materials, using salvaged items might be necessary.

- Cost-effectiveness: When budgets are tight, salvaged materials can be a way to save money on construction costs.

Remember:

- Always check local building codes and regulations to ensure compliance.

- Even without strict mandates, using salvaged materials can be a sustainable and creative choice for your project.

How is required Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

While there’s no universal mandate requiring a specific percentage of salvaged materials, here’s how the use of salvaged materials can be “required” or strongly encouraged:

1. Regulations and Codes:

- Historical Districts: In areas with historical significance, local regulations might mandate the use of salvaged materials to preserve the architectural character of the neighborhood.

- Specific Project Types: Some building codes might require or incentivize the use of salvaged materials for certain projects, like public buildings or those receiving public funding.

2. Green Building Standards:

- GGBC Certification: Programs like GGBC encourage the use of salvaged materials by awarding points towards certification. While not a strict requirement, maximizing salvaged materials can significantly boost a project’s GGBC rating.

- Other Certifications: Other green building standards may have similar incentives or guidelines for using salvaged materials.

3. Project-Specific Needs:

- Architectural Plans: Architects or clients might specify the use of salvaged materials in their project plans, driven by environmental concerns, aesthetic preferences, or budget considerations.

- Resource Availability: In regions where new materials are scarce or expensive, using salvaged items might be a practical necessity.

4. Contractual Obligations:

- Construction Contracts: Contracts with clients or developers might include clauses requiring the use of a certain percentage of salvaged materials.

It’s important to remember:

- Local laws always take precedence: Always check your local building codes and regulations for any specific requirements regarding salvaged materials.

- “Required” can mean different things: It might be a legal mandate, a condition for a certification, or a contractual obligation.

Even when not strictly “required,” using salvaged materials offers numerous benefits:

- Environmental responsibility: Reduces waste and the need for new resource extraction.

- Cost savings: Salvaged materials are often cheaper than new ones.

- Unique character: Adds a distinctive touch to any project.

By understanding the various ways salvaged materials can be “required,” you can make informed decisions about their use in your projects.

Case study is Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

While the concept of “Salvaged Materials 2.5%” might not be a common standard, it can be explored within the context of sustainable building practices and case studies. Here’s how:

1. Defining the Scope:

- Project Type: What kind of building is this? (Residential, commercial, public, etc.)

- Location: Where is the project located? (Regulations and material availability vary by region)

- Goals: What are the objectives? (Cost savings, environmental impact, historical preservation, etc.)

2. Identifying Opportunities:

- Material Availability: What types of salvaged materials are readily available in the area?

- Suitability: Which materials are suitable for the project’s needs and aesthetic goals?

- Feasibility: Is it practical to incorporate salvaged materials in terms of cost, logistics, and quality?

3. Setting Targets:

- Percentage Goal: While 2.5% might not be a mandate, it can serve as a starting point. The actual percentage will depend on the project’s specifics.

- Material Selection: Prioritize specific materials based on their environmental impact and suitability.

4. Implementation:

- Sourcing: Identify reliable sources for salvaged materials (demolition companies, salvage yards, etc.).

- Quality Control: Inspect and prepare salvaged materials to ensure they meet project standards.

- Integration: Incorporate salvaged materials seamlessly into the design and construction process.

5. Evaluation:

- Performance: Assess the performance of the building in terms of energy efficiency, durability, and occupant satisfaction.

- Environmental Impact: Measure the reduction in waste and resource consumption.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Analyze the cost savings achieved through the use of salvaged materials.

Example Case Study:

- Project: Renovation of a historic building in a city center.

- Goal: Preserve the building’s character while improving its sustainability.

- Salvaged Materials: Reclaimed wood flooring, antique doors and windows, vintage lighting fixtures.

- Outcome: The renovation successfully preserved the building’s historical charm, achieved a GGBC certification, and reduced construction costs.

By examining specific case studies, we can understand how salvaged materials are used in practice, the challenges and benefits involved, and how to set realistic targets for their incorporation in future projects.

COURTESY : Practical Engineering

White paper on Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

White Paper: Rethinking Construction – Exploring the Potential of Salvaged Materials (2.5% and Beyond)

Abstract:

The construction industry faces increasing pressure to adopt sustainable practices. This white paper challenges the conventional reliance on virgin materials and explores the potential of salvaged materials in achieving a more circular economy. While a fixed target like “2.5% salvaged materials” may not be universally applicable, this paper argues for a significant increase in the utilization of reclaimed resources, highlighting the benefits, challenges, and strategies for successful implementation.

1. Introduction:

The demand for raw materials in construction is depleting natural resources and contributing significantly to environmental degradation. A shift towards a circular economy, where materials are reused and repurposed, is crucial. Salvaged materials, reclaimed from demolition or deconstruction projects, offer a viable alternative to virgin resources, reducing waste, lowering environmental impact, and often adding unique character to buildings.

2. The Case for Salvaged Materials:

- Environmental Benefits: Reduced landfill waste, decreased energy consumption associated with manufacturing new materials, preservation of natural resources, and lower carbon footprint.

- Economic Advantages: Potential cost savings compared to purchasing new materials, creation of local jobs in deconstruction and material processing, and enhanced property value due to unique design elements.

- Social Impact: Preservation of historical and cultural heritage through the reuse of materials from older buildings, promotion of sustainable building practices within communities.

3. Beyond the 2.5% Target:

While a specific percentage like 2.5% can serve as a starting point for discussion, it shouldn’t be a limiting factor. The actual percentage of salvaged materials used should be determined by project-specific needs, material availability, and feasibility. A more holistic approach focusing on maximizing the use of reclaimed resources is necessary.

4. Challenges and Mitigation Strategies:

- Material Availability and Consistency: Sourcing sufficient quantities of suitable salvaged materials can be challenging. Mitigation: Develop robust material exchange platforms, promote deconstruction over demolition, and establish quality control standards for salvaged materials.

- Processing and Preparation: Salvaged materials often require cleaning, repair, or resizing. Mitigation: Invest in local processing facilities, train skilled labor in material restoration, and develop efficient processing techniques.

- Building Codes and Regulations: Existing codes may not always accommodate the use of salvaged materials. Mitigation: Advocate for code updates that recognize and encourage the use of reclaimed resources, develop standardized testing methods for salvaged materials.

- Perception and Acceptance: There may be a perception that salvaged materials are inferior or less reliable. Mitigation: Educate architects, contractors, and the public about the benefits and quality of salvaged materials, showcase successful projects featuring reclaimed resources.

5. Strategies for Implementation:

- Design for Deconstruction: Encourage building designs that facilitate future deconstruction and material reuse.

- Material Inventory and Tracking: Develop systems for tracking and cataloging salvaged materials to facilitate reuse.

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Foster collaboration between demolition contractors, salvage yards, architects, and builders.

- Incentives and Policies: Implement policies that incentivize the use of salvaged materials, such as tax breaks or grants.

6. Case Studies (Examples):

- [Insert Case Study 1]: A project showcasing the successful use of reclaimed wood in a residential building.

- [Insert Case Study 2]: A commercial building incorporating salvaged brick and metal.

7. Conclusion:

Moving beyond a fixed percentage target like 2.5%, this white paper advocates for a broader adoption of salvaged materials in the construction industry. By addressing the challenges and implementing the strategies outlined, we can unlock the full potential of reclaimed resources, creating a more sustainable and resilient built environment. Further research and development are needed to refine material processing techniques, establish standardized testing methods, and create a robust framework for integrating salvaged materials into mainstream construction practices.

8. Recommendations:

- Establish regional material exchange platforms.

- Develop training programs for deconstruction and material processing.

- Advocate for code updates that support the use of salvaged materials.

- Conduct further research on the long-term performance of buildings incorporating reclaimed resources.

This white paper provides a starting point for a broader conversation about the role of salvaged materials in sustainable construction. By embracing innovation and collaboration, we can create a future where buildings are not only structures but also repositories of valuable resources, contributing to a truly circular economy.

Industrial application of Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

You’re right to think about the industrial applications of salvaged materials! While the “2.5%” figure might not be a strict rule, the concept of reusing and repurposing materials is highly relevant in various industrial settings. Here’s how salvaged materials find their way into industrial applications:

1. Raw Material Substitution:

- Metals: Scrap metal (steel, aluminum, copper) is a major source of raw material for metal industries. It’s melted down and used to produce new metal products, reducing the need for mining virgin ore.

- Plastics: Recycled plastics are used in various industries, from packaging and automotive parts to construction materials.

- Glass: Recycled glass is used to make new glass containers, insulation, and even road aggregate.

- Paper: Recycled paper is a crucial component in the paper and packaging industry.

2. Manufacturing Processes:

- Construction: Reclaimed wood, brick, and concrete are used in new construction projects, reducing the demand for virgin materials and lowering construction costs.

- Furniture: Salvaged wood is often used to create unique and rustic furniture pieces.

- Art and Design: Artists and designers use salvaged materials to create sculptures, installations, and other art forms.

3. Energy Production:

- Waste-to-energy: Some industrial processes use waste materials, including salvaged wood and other organic matter, to generate energy.

4. Other Industrial Uses:

- Textiles: Reclaimed textiles are used to make new fabrics, insulation, and other products.

- Rubber: Recycled rubber is used in various applications, including flooring, playground surfaces, and tire production.

Examples of Industrial Applications:

- Steel industry: Uses vast amounts of scrap metal to produce new steel.

- Paper mills: Rely on recycled paper as a significant source of fiber.

- Plastic manufacturers: Utilize recycled plastics to create a wide range of products.

- Construction companies: Incorporate reclaimed wood and brick into building projects.

Benefits of Using Salvaged Materials in Industry:

- Resource conservation: Reduces the need to extract virgin resources.

- Waste reduction: Diverts materials from landfills.

- Energy efficiency: Often requires less energy to process salvaged materials compared to virgin resources.

- Cost savings: Salvaged materials can be more cost-effective than new materials.

By incorporating salvaged materials into their processes, industries can contribute to a more sustainable and circular economy.

Research and development of Salvaged Materials 2.5 % ?

You’re hitting on a really important point! While the idea of “Salvaged Materials 2.5%” might not be a standard, it highlights the need for more research and development in this area. Here’s why R&D is crucial for advancing the use of salvaged materials:

1. Overcoming Technical Challenges:

- Material Characterization: We need better methods to assess the quality and properties of salvaged materials. This includes developing standardized testing procedures for strength, durability, and potential contaminants.

- Processing and Upgrading: Research is needed to improve techniques for cleaning, repairing, and repurposing salvaged materials. This could involve developing new technologies for removing coatings, separating materials, and enhancing their performance.

- Integration and Compatibility: More research is needed to understand how salvaged materials can be effectively integrated into modern construction methods and ensure compatibility with other materials.

2. Enhancing Performance and Safety:

- Durability and Longevity: Research can help improve the durability and longevity of salvaged materials through treatments or modifications.

- Safety Concerns: Studies are needed to address potential safety concerns related to salvaged materials, such as the presence of lead, asbestos, or other hazardous substances.

- Structural Integrity: Research can help ensure the structural integrity of salvaged materials when used in construction, especially in critical applications.

3. Promoting Wider Adoption:

- Cost-Effectiveness: R&D can help make the use of salvaged materials more cost-effective by optimizing processing techniques and streamlining supply chains.

- Standardization and Certification: Research can contribute to the development of standards and certification programs for salvaged materials, increasing confidence among builders and consumers.

- Life Cycle Assessment: Conducting life cycle assessments can help quantify the environmental benefits of using salvaged materials and guide decision-making.

4. Exploring Innovative Applications:

- New Products and Technologies: R&D can lead to the development of new products and technologies that utilize salvaged materials in innovative ways.

- Circular Economy Models: Research can help create circular economy models for salvaged materials, where they are continuously reused and repurposed.

Examples of R&D efforts:

- Developing rapid testing methods for salvaged wood.

- Creating new composite materials from recycled plastics and other waste.

- Designing modular building systems that incorporate salvaged components.

- Investigating the use of salvaged materials in 3D printing for construction.

By investing in research and development, we can unlock the full potential of salvaged materials, making them a more viable and attractive option for a wide range of applications. This will contribute to a more sustainable and resource-efficient future.

COURTESY : DIY Network

References

- ^ Villalba, G; Segarra, M; Fernández, A.I; Chimenos, J.M; Espiell, F (December 2002). “A proposal for quantifying the recyclability of materials”. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 37 (1): 39–53. Bibcode:2002RCR….37…39V. doi:10.1016/S0921-3449(02)00056-3. ISSN 0921-3449.

- ^ Lienig, Jens; Bruemmer, Hans (2017). “Recycling Requirements and Design for Environmental Compliance”. Fundamentals of Electronic Systems Design. pp. 193–218. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55840-0_7. ISBN 978-3-319-55839-4.

- ^ European Commission (2014). “EU Waste Legislation”. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014.

- ^ Geissdoerfer, Martin; Savaget, Paulo; Bocken, Nancy M.P.; Hultink, Erik Jan (1 February 2017). “The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm?” (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 143: 757–768. Bibcode:2017JCPro.143..757G. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048. S2CID 157449142. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t League of Women Voters (1993). The Garbage Primer. New York: Lyons & Burford. pp. 35–72. ISBN 978-1-55821-250-3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lilly Sedaghat (4 April 2018). “7 Things You Didn’t Know About Plastic (and Recycling)”. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Aspden, Peter (9 December 2022). “Recycling Beauty, Prada Foundation — what the Romans did for us and what we did to them”. Financial Times. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Black Dog Publishing (2006). Recycle : a source book. London, UK: Black Dog Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904772-36-1.

- ^ Wood, J.R. (2022). “Approaches to interrogate the erased histories of recycled archaeological objects”. Archaeometry. 64: 187–205. doi:10.1111/arcm.12756. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n “The truth about recycling”. The Economist. 7 June 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Cleveland, Cutler J.; Morris, Christopher G. (15 November 2013). Handbook of Energy: Chronologies, Top Ten Lists, and Word Clouds. Elsevier. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-12-417019-3. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Dadd-Redalia, Debra (1 January 1994). Sustaining the earth: choosing consumer products that are safe for you, your family, and the earth. New York: Hearst Books. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-688-12335-2. OCLC 29702410.

- ^ Nongpluh, Yoofisaca Syngkon. (2013). Know all about : reduce, reuse, recycle. Noronha, Guy C.,, Energy and Resources Institute. New Delhi. ISBN 978-1-4619-4003-6. OCLC 858862026.

- ^ Carl A. Zimring (2005). Cash for Your Trash: Scrap Recycling in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4694-0.

- ^ “sd_shire” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Rethinking economic incentives for separate collection Archived 19 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Zero Waste Europe & Reloop Platform, 2017

- ^ “Report: “On the Making of Silk Purses from Sows’ Ears,” 1921: Exhibits: Institute Archives & Special Collections: MIT”. mit.edu. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “The War Episode 2: Rationing and Recycling”. Public Broadcasting System. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ “Out of the Garbage-Pail into the Fire: fuel bricks now added to the list of things salvaged by science from the nation’s waste”. Popular Science monthly. Bonnier Corporation. February 1919. pp. 50–51. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023.

- ^ “Recycling through the ages: 1970s”. Plastic Expert. 30 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “The price of virtue”. The Economist. 7 June 2007. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ “CRC History”. Computer Recycling Center. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ “About us”. Swico Recycling. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ “Where does e-waste end up?”. Greenpeace. 24 February 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kinver, Mark (3 July 2007). “Mechanics of e-waste recycling”. BBC. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ “Bulgaria opens largest WEEE recycling factory in Eastern Europe”. www.ask-eu.com. WtERT Germany GmbH. 12 July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2015.“EnvironCom opens largest WEEE recycling facility”. www.greenwisebusiness.co.uk. The Sixty Mile Publishing Company. 4 March 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.Goodman, Peter S. (11 January 2012). “Where Gadgets Go To Die: E-Waste Recycler Opens New Plant in Las Vegas”. Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2015.[unreliable source?]Moses, Asher (19 November 2008). “New plant tackles our electronic leftovers”. Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ European Commission, Recycling Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ “Recycling rates in Europe”. European Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ “Recycling of municipal waste”. European Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Paben, Jared (7 February 2017). “Germany’s recycling rate continues to lead Europe”. Resource Recycling News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ Hook, Leslie; Reed, John (24 October 2018). “Why the world’s recycling system stopped working”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ “Electronic waste (e-waste)”. World Health Organization (WHO). 18 October 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Patil T., Rebaioli L., Fassi I., “Cyber-physical systems for end-of-life management of printed circuit boards and mechatronics products in home automation: A review” Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2022.

- ^ Solomon Gabasiane, Tlotlo; Danha, Gwiranai; A. Mamvura, Tirivaviri; et al. (2021). Dang, Prof. Dr. Jie; Li, Dr. Jichao; Lv, Prof. Dr. Xuewei; Yuan, Prof. Dr. Shuang; Leszczyńska-Sejda, Dr. Katarzyna (eds.). “Environmental and Socioeconomic Impact of Copper Slag—A Review”. Crystals. 11 (12): 1504. doi:10.3390/cryst11121504. This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Edraki, Mansour; Baumgarti, Thomas; Manlapig, Emmanuel; Bradshaw, Dee; M. Franks, Daniel; J. Moran, Chris (December 2014). “Designing mine tailings for better environmental, social and economic outcomes: a review of alternative approaches”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 84: 411–420. Bibcode:2014JCPro..84..411E. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.04.079 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Shen, Huiting; Forssberg (2003). “An overview of recovery of metals from slags”. Waste Management. 23 (10): 933–949. Bibcode:2003WaMan..23..933S. doi:10.1016/S0956-053X(02)00164-2. PMID 14614927.

- ^ Mahar, Amanullah; Wang, Ping; Ali, Amjad; Kumar Awasthi, Mukesh; Hussain Lahori, Altaf; Wang, Quan; Li, Ronghua; Zhang, Zengqiang (April 2016). “Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A review”. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 126: 111–121. Bibcode:2016EcoES.126..111M. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.12.023. PMID 26741880 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Khalid, Sana; Shahid, Muhammad; Khan Niazi, Nabeel; Murtaza, Behzad; Bibi, Irshad; Dumat, Camille (November 2017). “A comparison of technologies for remediation of heavy metal contaminated soils”. Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 182 (Part B): 247–268. Bibcode:2017JCExp.182..247K. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2016.11.021.

- ^ “Slag Recycling”. Recovery Worldwide.

- ^ Landsburg, Steven E. (2012). “Why I Am Not An Environmentalist”. The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life. Simon and Schuster. pp. 279–290. ISBN 978-1-4516-5173-7. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Steven E. Landsburg (May 2012). The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4516-5173-7. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Baird, Colin (2004). Environmental Chemistry (3rd ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4877-0.[page needed]

- ^ de Jesus, Simeon (1975). “How to make paper in the tropics”. Unasylva. 27 (3). Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ UNFCCC (2007). “Investment and financial flows to address climate change” (PDF). unfccc.int. UNFCCC. p. 81. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Towie, Narelle (28 February 2019). “Burning issue: are waste-to-energy plants a good idea?”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ “A Beverage Container Deposit Law for Hawaii”. www.opala.org. City & County of Honolulu, Department of Environmental Services. October 2002. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ European Council. “The Producer Responsibility Principle of the WEEE Directive” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ “Regulatory Policy Center — Property Matters — James V. DeLong”. Archived from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ^ Web-Dictionary.com (2013). “Recyclate”. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Freudenrich, C. (2014) (14 December 2007). “How Plastics Work”. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f “Quality Action Plan Proposals to Promote High Quality Recycling of Dry Recyclates” (PDF). DEFRA. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ “How to Recycle Tin or Steel Cans”. Earth911. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Recyclate Quality Action Plan – Consultation Paper”. The Scottish Government. 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013.

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (1 October 2020). “One bin future: How mixing trash and recycling can work”. Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-092920-3. S2CID 224860591. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ “The State of Multi-Tenant Recycling in Oregon” (PDF). April 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Baechler, Christian; DeVuono, Matthew; Pearce, Joshua M. (2013). “Distributed Recycling of Waste Polymer into RepRap Feedstock”. Rapid Prototyping Journal. 19 (2): 118–125. doi:10.1108/13552541311302978. S2CID 15980607. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Kreiger, M.; Anzalone, G. C.; Mulder, M. L.; Glover, A.; Pearce, J. M. (2013). “Distributed Recycling of Post-Consumer Plastic Waste in Rural Areas”. MRS Online Proceedings Library. 1492: 91–96. doi:10.1557/opl.2013.258. ISSN 0272-9172. S2CID 18303920. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Kreiger, M.A.; Mulder, M.L.; Glover, A.G.; Pearce, J. M. (2014). “Life Cycle Analysis of Distributed Recycling of Post-consumer High Density Polyethylene for 3-D Printing Filament”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 70: 90–96. Bibcode:2014JCPro..70…90K. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.009. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ Insider Business (12 October 2021). Young Inventor Makes Bricks From Plastic Trash. World Wide Waste. Retrieved 26 February 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ Kumar, Rishabh; Kumar, Mohit; Kumar, Inder; Srivastava, Deepa (2021). “A review on utilization of plastic waste materials in bricks manufacturing process”. Materials Today: Proceedings. 46: 6775–6780. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.04.337. S2CID 236599187.

- ^ Chauhan, S S; Kumar, Bhushan; Singh, Prem Shankar; Khan, Abuzaid; Goyal, Hritik; Goyal, Shivank (1 November 2019). “Fabrication and Testing of Plastic Sand Bricks”. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 691 (1): 012083. Bibcode:2019MS&E..691a2083C. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/691/1/012083. ISSN 1757-899X. S2CID 212846044.

- ^ Tsala-Mbala, Celestin; Hayibo, Koami Soulemane; Meyer, Theresa K.; Couao-Zotti, Nadine; Cairns, Paul; Pearce, Joshua M. (October 2022). “Technical and Economic Viability of Distributed Recycling of Low-Density Polyethylene Water Sachets into Waste Composite Pavement Blocks”. Journal of Composites Science. 6 (10): 289. doi:10.3390/jcs6100289. ISSN 2504-477X.

- ^ Samson, Sam (19 February 2023). “Single-use face masks get new life thanks to Regina engineer”. CBC.

- ^ “How recycling robots have spread across North America”. Resource Recycling News. 7 May 2019. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ “AMP Robotics announces largest deployment of AI-guided recycling robots”. The Robot Report. 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ None, None (10 August 2015). “Common Recyclable Materials” (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ “Recycling Without Sorting: Engineers Create Recycling Plant That Removes The Need To Sort”. ScienceDaily. 1 October 2007. Archived from the original on 31 August 2008.

- ^ “Sortation by the numbers”. Resource Recycling News. 1 October 2018. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Goodship, Vannessa (2007). Introduction to Plastics Recycling. iSmithers Rapra Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84735-078-7.[page needed]

- ^ None, None. “What Happens to My Recycling?”. 1coast.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ “Best Recycling Programs in the US & Around the World”. cmfg.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ “Mayor Lee Announces San Francisco Reaches 80 Percent Landfill Waste Diversion, Leads All Cities in North America”. San Francisco Department of the Environment. 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ “UK statistics on waste – 2010 to 2012” (PDF). UK Government. 25 September 2014. p. 2 and 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Polymer modified cements and repair mortars. Daniels LJ, PhD thesis Lancaster University 1992

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Publications – International Resource Panel”. unep.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ “How Urban Mining Works”. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ McDonald, N. C.; Pearce, J. M. (2010). “Producer Responsibility and Recycling Solar Photovoltaic Modules” (PDF). Energy Policy. 38 (11): 7041–7047. Bibcode:2010EnPol..38.7041M. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.07.023. hdl:1974/6122. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Hogye, Thomas Q. “The Anatomy of a Computer Recycling Process” (PDF). California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ “Sweeep Kuusakoski – Resources – BBC Documentary”. www.sweeepkuusakoski.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ “Sweeep Kuusakoski – Glass Recycling – BBC filming of CRT furnace”. www.sweeepkuusakoski.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b The dark side of green energies documentary

- ^ Layton, Julia (22 April 2009). “”Eco”-plastic: recycled plastic”. Science.howstuffworks.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Francisco José Gomes da Silva; Ronny Miguel Gouveia (18 July 2019). Cleaner Production: Toward a Better Future. Springer. p. 180. ISBN 978-3-03-023165-1. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Timothy E. Long; John Scheirs (1 September 2005). Modern Polyesters: Chemistry and Technology of Polyesters and Copolyesters. John Wiley & Sons. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-470-09067-1. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Werner, Debra (21 October 2019). “Made in Space to launch commercial recycler to space station”. SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Siegel, R. P. (7 August 2019). “Eastman advances two chemical recycling options”. GreenBiz. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ “RESEM A Leading Pyrolysis Plant Manufacturer”. RESEM Pyrolysis Plant. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Plastic Recycling codes Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, American Chemistry

- ^ About resin identification codes Archived 19 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine American Chemistry

- ^ “Recycling Symbols on Plastics – What Do Recycling Codes on Plastics Mean”. The Daily Green. 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Unless otherwise indicated, this data is taken from The League of Women Voters (1993). The Garbage Primer. New York: Lyons & Burford. pp. 35–72. ISBN 978-1-55821-250-3., which attributes, “Garbage Solutions: A Public Officials Guide to Recycling and Alternative Solid Waste Management Technologies, as cited in Energy Savings from Recycling, January/February 1989; and Worldwatch 76 Mining Urban Wastes: The Potential for Recycling, April 1987.”

- ^ “Recycling metals — aluminium and steel”. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ “UCO: Recycling”. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ “From Waste to Jobs: What Achieving 75 Percent Recycling Means for California” (PDF). March 2014. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ “Recycling Benefits to the Economy”. all-recycling-facts.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Daniel K. Benjamin (2010). “Recycling myths revisited”. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ “A Recycling Revolution”. recycling-revolution.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Lavee, Doron (26 November 2007). “Is Municipal Solid Waste Recycling Economically Efficient?”. Environmental Management. 40 (6): 926–943. Bibcode:2007EnMan..40..926L. doi:10.1007/s00267-007-9000-7. PMID 17687596. S2CID 40085245.

- ^ Vigso, Dorte (2004). “Deposits on single use containers — a social cost–benefit analysis of the Danish deposit system for single use drink containers”. Waste Management & Research. 22 (6): 477–87. Bibcode:2004WMR….22..477V. doi:10.1177/0734242X04049252. PMID 15666450. S2CID 13596709.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Gunter, Matthew (1 January 2007). “Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Household and Municipal Recycling?”. Econ Journal Watch. 4 (1): 83–111. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Alt URL Archived 15 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to:a b Howard Husock (23 June 2020). “The Declining Case for Municipal Recycling”. Foundation for Economic Education. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Serena Ng and Angela Chen (29 April 2015). “Unprofitable Recycling Weighs On Waste Management”. Wall Street Journal.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Daniel K. Benjamin (2010). “Recycling and waste have $6.7 billion economic impact in Ohio” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ “Much toxic computer waste lands in Third World”. USA Today. Associated Press. 25 February 2002. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007.

- ^ Gough, Neil (11 March 2002). “Garbage In, Garbage Out”. Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 November 2003.

- ^ Illegal dumping and damage to health and environment. CBC. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012.

- ^ Hogg, Max (15 May 2009). “Waste outshines gold as prices surge”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Desimone, Bonnie (21 February 2006). “Rewarding Recyclers, and Finding Gold in the Garbage”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Tracy, Ben (14 April 2024). “Critics call out plastics industry over “fraud of plastic recycling””. CBS News. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Afterlife: An Essential Guide To Design For Disassembly, by Alex Diener

- ^ “Fact Sheets on Designing for the Disassembly and Deconstruction of Buildings”. epa.gov. EPA. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Huesemann, Michael H. (2003). “The limits of technological solutions to sustainable development”. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy. 5 (1): 21–34. Bibcode:2003CTEP….5…21H. doi:10.1007/s10098-002-0173-8. S2CID 55193459.

- ^ Tierney, John (30 June 1996). “Recycling Is Garbage”. The New York Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ^ Rosenberg, Mike (23 April 2019). “Largest e-recycling fraud in U.S. history sends owners of Kent firm to prison”. The Seattle Times. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Lynn R. Kahle; Eda Gurel-Atay, eds. (2014). Communicating Sustainability for the Green Economy. New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3680-5.

- ^ Morris, Jeffrey (1 July 2005). “Comparative LCAs for Curbside Recycling Versus Either Landfilling or Incineration with Energy Recovery (12 pp)”. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 10 (4): 273–284. Bibcode:2005IJLCA..10..273M. doi:10.1065/lca2004.09.180.10. S2CID 110948339.

- ^ Oskamp, Stuart (1995). “Resource Conservation and Recycling: Behavior and Policy”. Journal of Social Issues. 51 (4): 157–177. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01353.x.

- ^ Pimenteira, C.A.P.; Pereira, A.S.; Oliveira, L.B.; Rosa, L.P.; Reis, M.M.; Henriques, R.M. (2004). “Energy conservation and CO2 emission reductions due to recycling in Brazil”. Waste Management. 24 (9): 889–897. Bibcode:2004WaMan..24..889P. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2004.07.001. PMID 15504666.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brown, M.T.; Buranakarn, Vorasun (2003). “Emergy indices and ratios for sustainable material cycles and recycle options”. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 38 (1): 1–22. Bibcode:2003RCR….38….1B. doi:10.1016/S0921-3449(02)00093-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Recycling paper and glass”, Energy Kid’s Page, U.S. Energy Information Administration, archived from the original on 25 October 2008

- ^ Decker, Ethan H.; Elliott, Scott; Smith, Felisa A.; Blake, Donald R.; Rowland, F. Sherwood (November 2000). “Energy and Material flow through the urban Ecosystem”. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 25 (1): 685–740. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.582.2325. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.25.1.685. OCLC 42674488.

- ^ “How does recycling save energy?”. Municipal Solid Waste: Frequently Asked Questions about Recycling and Waste Management. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- ^ Margolis, Nancy (July 1997). “Energy and Environmental Profile of the U.S. Aluminum Industry” (PDF). US Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2011.

- ^ Lerche, Jacqueline (2011). “The Recycling of Aluminum Cans Versus Plastic”. National Geographic Green Living. Demand Media. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011.

- ^ “By the Numbers”. Can Manufacturers Institute. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019.

- ^ Brunner, P. H. (1999). “In search of the final sink”. Environ. Sci. & Pollut. Res. 6 (1): 1. Bibcode:1999ESPR….6….1B. doi:10.1007/bf02987111. PMID 19005854. S2CID 46384723.

- ^ Landsburg, Steven E. The Armchair Economist. p. 86.

- ^ Selke 116[full citation needed]

- ^ Grosse, François; Mainguy, Gaëll (2010). “Is recycling ‘part of the solution’? The role of recycling in an expanding society and a world of finite resources”. S.A.P.I.EN.S. 3 (1): 1–17. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ Sahni, S.; Gutowski, T. G. (2011). “Your scrap, my scrap! The flow of scrap materials through international trade” (PDF). IEEE International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technology (ISSST). pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ISSST.2011.5936853. ISBN 978-1-61284-394-0. S2CID 2435609. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Lehmann, Steffen (15 March 2011). “Resource Recovery and Materials Flow in the City: Zero Waste and Sustainable Consumption as Paradigms in Urban Development”. Sustainable Development Law & Policy. 11 (1). Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Zaman, A. U.; Lehmann, S. (2011). “Challenges and opportunities in transforming a city into a ‘Zero Waste City'”. Challenges. 2 (4): 73–93. doi:10.3390/challe2040073.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Huesemann, M.; Huesemann, J. (2011). Techno-fix: Why Technology Won’t Save Us or the Environment. New Society Publishers. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-86571-704-6. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Clark, Brett; Foster, John Bellamy (2009). “Ecological Imperialism and the Global Metabolic Rift: Unequal Exchange and the Guano/Nitrates Trade”. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 50 (3–4): 311–334. doi:10.1177/0020715209105144. S2CID 154627746.

- ^ Foster, John Bellamy; Clark, Brett (2011). The Ecological Rift: Capitalisms War on the Earth. Monthly Review Press. p. 544. ISBN 978-1-58367-218-1. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023.

- ^ Alcott, Blake (2005). “Jevons’ paradox”. Ecological Economics. 54 (1): 9–21. Bibcode:2005EcoEc..54….9A. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.03.020. hdl:1942/22574.

- ^ Tierney, John (30 June 1996). “Recycling is Garbage”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ “The Five Most Dangerous Myths About Recycling”. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. 14 September 1996. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ “Markets for Recovered Glass”. National Service Center for Environmental Publications. US Environmental Protection Agency. December 1992. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023.

- ^ Bolen, Wallace P. (January 1998). “Sand and Gravel (Industrial)” (PDF). In National Minerals Information Center (ed.). Mineral Commodity Summaries. Silica Statistics and Information. U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 146–147. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Sepúlveda, Alejandra; Schluep, Mathias; Renaud, Fabrice G.; Streicher, Martin; Kuehr, Ruediger; Hagelüken, Christian; Gerecke, Andreas C. (2010). “A review of the environmental fate and effects of hazardous substances released from electrical and electronic equipments during recycling: Examples from China and India”. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 30 (1): 28–41. Bibcode:2010EIARv..30…28S. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2009.04.001.

- ^ “Too Good To Throw Away – Appendix A”. NRDC. 30 June 1996. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ “Mission Police Station” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c PBS NewsHour, 16 February 2010. Report on the Zabaleen

- ^ Medina, Martin (2000). “Scavenger cooperatives in Asia and Latin America”. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 31 (1): 51–69. Bibcode:2000RCR….31…51M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.6981. doi:10.1016/s0921-3449(00)00071-9.

- ^ “The News-Herald – Scrap metal a steal”. Zwire.com. Retrieved 6 November 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ “Raids on Recycling Bins Costly To Bay Area”. NPR. 19 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Burn, Shawn (2006). “Social Psychology and the Stimulation of Recycling Behaviors: The Block Leader Approach”. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 21 (8): 611–629. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.1934. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1991.tb00539.x.

- ^ Oskamp, Stuart (1995). “Resource Conservation and Recycling: Behavior and Policy”. Journal of Social Issues. 51 (4): 157–177. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01353.x.

- ^ Recycling Rates of Metals: A status report. United Nations Environment Programme. 2011. ISBN 978-92-807-3161-3. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Moore, C. J. (2008). “Synthetic polymers in the marine environment: A rapidly increasing, long-term threat”. Environmental Research. 108 (2): 131–139. Bibcode:2008ER….108..131M. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2008.07.025. PMID 18949831. S2CID 26874262.

- ^ Schackelford, T.K. (2006). “Recycling, evolution and the structure of human personality”. Personality and Individual Differences. 41 (8): 1551–1556. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.07.020.

- ^ Pratarelli, Marc E. (4 February 2010). “Social pressure and recycling: a brief review, commentary and extensions”. S.A.P.I.EN.S. 3 (1). Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Saabira (19 December 2019). “Recycling Rethink: What to Do With Trash Now That China Won’t Take It”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Negrete-Cardoso, Mariana; Rosano-Ortega, Genoveva; Álvarez-Aros, Erick Leobardo; Tavera-Cortés, María Elena; Vega-Lebrún, Carlos Arturo; Sánchez-Ruíz, Francisco Javier (1 September 2022). “Circular economy strategy and waste management: a bibliometric analysis in its contribution to sustainable development, toward a post-COVID-19 era”. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 29 (41): 61729–61746. Bibcode:2022ESPR…2961729N. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-18703-3. ISSN 1614-7499. PMC 9170551. PMID 35668274.

- ^ K, J, P, Melati, Nikam, Nguyen. “arriers and drivers for enterprises to transition to a circular economy. Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden” (PDF). Arriers and Drivers for Enterprises to Transition to a Circular Economy. Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden.