Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

When discussing “least outside air ventilation,” it’s crucial to understand that ventilation requirements are designed to ensure acceptable indoor air quality. These requirements vary significantly depending on:

- Occupancy type: Different spaces (offices, schools, hospitals, etc.) have different ventilation needs.

- Occupant density: More people in a space mean a greater need for fresh air.

- Building codes and standards: Organizations like ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers) publish standards that define minimum ventilation rates.

Here’s a breakdown of key concepts:

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1:

- This standard is a primary source for ventilation requirements in commercial and institutional buildings.

- It specifies minimum outdoor air rates to dilute indoor air contaminants.

- The rates are typically expressed in cubic feet per minute (cfm) per person or per square foot.

- Purpose of Ventilation:

- To remove pollutants generated indoors.

- To dilute carbon dioxide (CO2) exhaled by occupants.

- To control humidity.

- Factors affecting ventilation:

- Natural ventilation (opening windows)

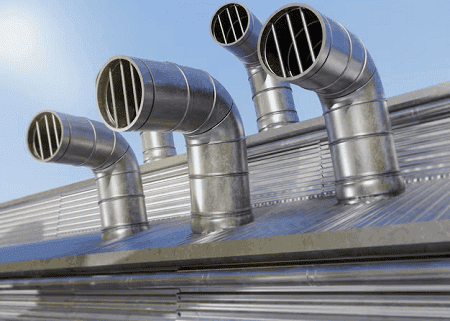

- Mechanical ventilation (HVAC systems)

Key points from the search results:

- Ventilation rates are not a single, fixed number. They vary greatly.

- ASHRAE standards provide guidelines for minimum ventilation rates, which are important for indoor air quality.

- Energy efficiency is also a consideration. Over ventilation increases energy consumption, so finding the optimal balance is important.

If you have a specific type of space in mind (e.g., a classroom, office, or restaurant), I can provide more targeted information.

What is Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

It’s important to clarify that “Least Outside Air Ventilation 23” isn’t a universally defined, standalone term. Ventilation requirements are complex and depend on various factors. However, I can provide context to help understand the concept:

Key Concepts:

- ASHRAE Standards:

- The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) publishes standards, particularly ASHRAE Standard 62.1, which set guidelines for minimum ventilation rates.

- These standards aim to ensure acceptable indoor air quality.

- Ventilation Rates:

- Ventilation rates are typically expressed in cubic feet per minute (cfm) and can be based on:

- Cfm per person.

- Cfm per square foot.

- The required ventilation rate varies significantly depending on the type of space (e.g., office, classroom, hospital).

- Ventilation rates are typically expressed in cubic feet per minute (cfm) and can be based on:

- Purpose of Ventilation:

- To remove indoor air pollutants.

- To dilute carbon dioxide (CO2).

- To control humidity.

Factors Influencing Ventilation:

- Occupancy: The number of people in a space.

- Activity Level: Higher activity levels generate more pollutants.

- Building Codes: Local and national building codes.

In essence:

- When discussing “least outside air ventilation,” we’re talking about the minimum amount of fresh, outdoor air that must be brought into a space to maintain acceptable indoor air quality.

- The number 23, without more context, likely refers to a specific value within a particular ventilation calculation, or a table of ventilation rates. It is not a general standard.

- ASHRAE standards provide detailed tables of ventilation rates that vary by the use of the space.

Therefore, to understand the meaning of “Least Outside Air Ventilation 23” in a specific situation, it would be necessary to know the context in which it is used.

Who is required Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

When discussing ventilation requirements, particularly those outlined by ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers), it’s not accurate to say a specific number like “23” applies to a single group. Instead, ventilation standards apply broadly to those responsible for:

- Building Design and Construction:

- Architects and engineers who design HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems.

- Construction contractors who install those systems.

- Building Owners and Operators:

- Those responsible for maintaining and operating buildings to ensure proper ventilation.

- Facility Managers:

- Individuals tasked with overseeing the day-to-day operations of buildings, including ventilation system performance.

- Regulatory Authorities:

- Building code officials who enforce ventilation standards.

Here’s a breakdown of how ASHRAE standards, particularly ASHRAE Standard 62.1, come into play:

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1:

- This standard sets minimum ventilation rates to ensure acceptable indoor air quality in commercial and institutional buildings.

- It’s intended to be used by those involved in the design, installation, and operation of ventilation systems.

- Therefore, anyone responsible for these aspects of a building is effectively “required” to adhere to these standards, often through local building codes.

Key takeaways:

- Ventilation requirements are not specific to a single profession but apply to a wide range of individuals and organizations involved in building design, construction, and operation.

- ASHRAE standards provide the guidelines, and local building codes often mandate compliance.

Therefore, rather than one group being required to a number, many groups are required to follow the standards that provide numbers that change depending on the use of the space.

When is required Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

It’s important to understand that ventilation requirements, as outlined by ASHRAE, are ongoing and not tied to a single, specific moment. They are required whenever a building is occupied. Here’s a breakdown:

When Ventilation is Required:

- During Occupancy:

- The primary purpose of ventilation is to ensure healthy indoor air quality for occupants. Therefore, ventilation systems must operate whenever people are present in a building.

- This includes:

- Regular business hours in offices.

- School hours in educational facilities.

- Operating hours in retail stores and restaurants.

- Continuous Operation (in some cases):

- In certain environments, such as hospitals or laboratories, continuous ventilation is crucial to maintain critical air quality levels.

- Even in other buildings, minimum levels of ventilation may be required outside of occupied hours to prevent the buildup of pollutants or moisture.

- During Building Design and Construction:

- Ventilation requirements must be considered from the initial design phase of a building.

- Architects and engineers must design HVAC systems that comply with ASHRAE standards and local building codes.

- During construction, proper installation and testing of ventilation systems are essential.

- During Building Operation and Maintenance:

- Ongoing maintenance of ventilation systems is necessary to ensure they continue to operate effectively.

- This includes:

- Regular filter changes.

- System inspections.

- Airflow measurements.

Key Considerations:

- ASHRAE Standards:

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1 provides the guidelines for minimum ventilation rates, which are intended to be followed consistently.

- These standards are updated periodically to reflect new research and best practices.

- Building Codes:

- Local building codes often adopt ASHRAE standards, making them legally enforceable.

In essence, “Least Outside Air Ventilation” is a continuous requirement, not a one-time event. It’s an integral part of maintaining healthy and comfortable indoor environments.

COURTESY :HVAC Easy Math

Where is required Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

It’s more accurate to discuss where ventilation, in general, is required, rather than focusing on a specific numerical value like “23.” Ventilation requirements apply to a wide range of indoor spaces. Here’s a general overview:

Where Ventilation Is Required:

- Commercial Buildings:

- Offices

- Retail stores

- Restaurants

- Hotels

- Theaters

- Institutional Buildings:

- Schools and universities

- Hospitals and healthcare facilities

- Government buildings

- Residential Buildings:

- Homes and apartments (though requirements may differ from commercial buildings)

- Industrial Facilities:

- Factories

- Warehouses

- Manufacturing plants (where specific processes may generate pollutants)

- Any Occupied Space:

- Essentially, any indoor space where people spend time requires ventilation to ensure acceptable indoor air quality.

Key Factors:

- Occupancy:

- Spaces with higher occupant densities require more ventilation.

- Activity Levels:

- Spaces where people engage in strenuous activities (e.g., gyms) require increased ventilation.

- Potential Pollutant Sources:

- Spaces where pollutants are generated (e.g., kitchens, laboratories) require enhanced ventilation.

Important Considerations:

- ASHRAE Standards:

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1 provides detailed guidelines for ventilation in various building types.

- Building Codes:

- Local building codes often adopt ASHRAE standards, making them legally enforceable.

Therefore, ventilation is a widespread requirement across virtually all types of buildings where people are present.

How is required Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

Understanding how “Least Outside Air Ventilation” is required involves looking at the processes and standards that govern ventilation systems. Here’s a breakdown:

Key Processes and Standards:

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1:

- This standard is fundamental. It provides the calculations and guidelines for determining the minimum amount of outdoor air required for acceptable indoor air quality.

- It involves calculating ventilation rates based on:

- Occupancy density (number of people)

- Floor area

- The specific activities taking place in the space

- Calculations:

- The process involves mathematical calculations to determine the required airflow in cubic feet per minute (cfm).

- These calculations take into account both the number of occupants and the size of the space.

- The formula used includes factors for:

- Outdoor airflow rate per person

- Outdoor airflow rate per unit area

- HVAC System Design:

- Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems are designed to deliver the required amount of outdoor air.

- Engineers use ASHRAE standards to select and size equipment, such as:

- Air handling units

- Ductwork

- Fans

- Building Codes and Regulations:

- Local building codes often adopt ASHRAE standards, making them legally enforceable.

- Building inspectors verify that ventilation systems meet the required standards.

- System Operation and Maintenance:

- Once installed, ventilation systems must be properly operated and maintained to ensure they continue to deliver the required airflow.

- This includes:

- Regular filter changes

- System inspections

- Airflow measurements

In essence:

- Ventilation requirements are implemented through a combination of engineering design, building codes, and ongoing maintenance.

- ASHRAE standards provide the technical basis for these requirements.

- It is not a simple matter of just having a number, but following a set of standards that provide the correct calculations, and then designing and installing the correct HVAC systems to provide the needed ventilation.

I hope this explanation is helpful.

Case study is Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

It’s important to clarify that “Least Outside Air Ventilation 23” as a specific, isolated case study is not how ventilation standards are typically applied. Instead, ASHRAE Standard 62.1 provides a framework, and real-world applications of this standard become the “case studies.” Here’s how to understand this:

Understanding ASHRAE 62.1 in Practice:

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1 as the Foundation:

- This standard provides the methods and calculations for determining appropriate ventilation rates.

- It’s used by engineers and designers to create ventilation systems that meet specific building and occupancy needs.

- Real-World Applications as “Case Studies”:

- Every building where ASHRAE 62.1 is implemented becomes a practical example of its application.

- These “case studies” involve:

- Designing ventilation systems for different building types (offices, schools, hospitals).

- Addressing unique challenges, such as high occupancy density or specific pollutant sources.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of ventilation systems in maintaining indoor air quality.

- Key Aspects of These “Case Studies”:

- Variability:

- Ventilation requirements change based on the space. A classroom will have different needs than a warehouse.

- Therefore, each building project is, in a way, its own case study.

- Compliance:

- Building inspectors check if ventilation systems meet ASHRAE 62.1 standards and local building codes.

- This compliance process results in many real-world examples of the standard’s application.

- Optimization:

- Engineers work to balance ventilation with energy efficiency.

- This optimization process creates examples of how to achieve both healthy indoor air and sustainable building operations.

- Variability:

Where to Find Examples:

- ASHRAE Publications:

- ASHRAE publishes journals, handbooks, and other resources that include case studies and practical applications of its standards.

- Engineering Firms:

- HVAC engineering firms have extensive experience designing and implementing ventilation systems.

- Their projects serve as real-world examples of ASHRAE 62.1 in action.

- Building Performance Assessments:

- Studies that evaluate the indoor air quality of buildings often reference ASHRAE 62.1.

- Those studies can be considered case studies of how well or how poorly a building complies with the ventilation standards.

In summary, rather than a single “case study,” the application of ASHRAE 62.1 creates a multitude of real-world examples that demonstrate its principles.

COURTESY : MEP Academy

White paper on Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

It’s important to understand that when looking for information on “Least Outside Air Ventilation,” you’ll find resources that discuss the broader principles of ventilation, rather than documents specifically titled with that exact phrase and a numerical value like “23.” Ventilation standards are complex and vary greatly.

Here’s a breakdown of where to find relevant information, and what those resources typically contain:

Key Sources of Information:

- ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers):

- ASHRAE is the primary source for ventilation standards. Their publications, particularly ASHRAE Standard 62.1, provide detailed guidelines.

- You can find white papers, research reports, and standards documents on their website. These documents cover topics like:

- Minimum ventilation rates for different building types.

- Indoor air quality and its impact on health.

- Energy-efficient ventilation strategies.

- Therefore when searching for very reliable information, ASHRAE is the best source.

- Government Agencies:

- Agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States provide information on indoor air quality and ventilation.

- They may publish white papers and guidelines on topics such as:

- The health effects of indoor air pollutants.

- Ventilation strategies for reducing exposure to pollutants.

- Research Institutions:

- Universities and research organizations conduct studies on ventilation and indoor air quality.

- Their findings are often published in peer-reviewed journals and white papers.

What These Resources Typically Cover:

- Fundamentals of Ventilation:

- The importance of outdoor air for diluting indoor pollutants.

- The relationship between ventilation and health.

- Ventilation Standards and Guidelines:

- Detailed information on minimum ventilation rates and how to calculate them.

- Guidance on designing and operating ventilation systems.

- Advanced Ventilation Strategies:

- Topics such as demand-controlled ventilation and energy recovery ventilation.

- Information on how to optimize ventilation for both indoor air quality and energy efficiency.

Key Considerations:

- When searching for information, use keywords such as “ASHRAE 62.1,” “indoor air quality,” and “ventilation standards.”

- Be aware that ventilation requirements can vary depending on local building codes and regulations.

I hope this helps.

Industrial application of Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

When considering the industrial application of ventilation, it’s crucial to move away from the idea of a fixed number like “23” and focus on the principles of adequate air exchange. Industrial settings present unique ventilation challenges due to the potential for:

- Hazardous materials:

- Factories may produce or use chemicals, fumes, dust, or other pollutants.

- Proper ventilation is essential to dilute and remove these contaminants, protecting worker health.

- Heat generation:

- Industrial processes often generate significant heat.

- Ventilation helps to remove excess heat and maintain comfortable working conditions.

- Specific process requirements:

- Certain industrial processes, such as painting or welding, require specialized ventilation systems.

Here’s how ventilation principles are applied in industrial settings:

Key Industrial Applications:

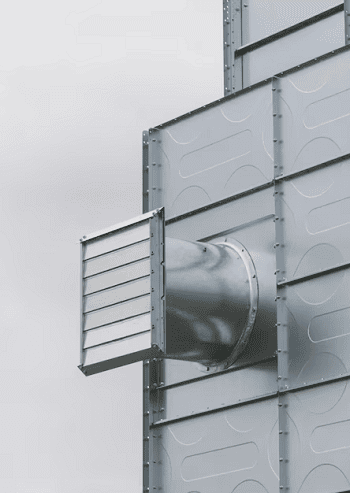

- Local Exhaust Ventilation:

- This involves capturing pollutants at their source using hoods and ductwork.

- Examples include:

- Welding fume extraction.

- Spray booth ventilation.

- Dust collection systems.

- General Ventilation:

- This involves providing a general flow of fresh air throughout the workspace.

- It helps to dilute pollutants that are not captured by local exhaust systems.

- Hazardous Area Ventilation:

- In areas where flammable gases or vapors are present, specialized ventilation systems are required to prevent explosions.

- These systems must be designed to meet strict safety standards.

- Cleanroom Ventilation:

- Industries such as pharmaceuticals and electronics require cleanrooms with highly controlled ventilation systems.

- These systems use HEPA filters to remove airborne particles and maintain a sterile environment.

Important Considerations:

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA):

- In the United States, OSHA sets standards for workplace safety, including ventilation requirements.

- Similar agencies exist in other countries.

- ASHRAE Standards:

- ASHRAE standards provide guidance on ventilation system design and operation.

- Risk Assessment:

- Industrial facilities should conduct thorough risk assessments to identify potential hazards and determine appropriate ventilation requirements.

In essence, industrial ventilation is a complex field that requires careful consideration of specific hazards and processes. It’s about designing and implementing systems that protect workers and ensure safe operating conditions.

Research and development of Least Outside Air Ventilation 23 ?

The research and development (R&D) of ventilation systems, especially concerning “least outside air ventilation” in the context of optimizing indoor air quality and energy efficiency, is a dynamic and evolving field. Here’s a summary of key areas of R&D:

Key Research Areas:

- Demand-Controlled Ventilation (DCV):

- R&D focuses on improving sensor technology (e.g., CO2 sensors, VOC sensors) to accurately assess indoor air quality in real-time.

- Algorithms are being developed to optimize ventilation rates based on actual occupancy and pollutant levels, minimizing energy waste.

- Advanced Filtration Technologies:

- Research is ongoing to develop more efficient and effective air filtration systems, including HEPA filters and other advanced filtration media.

- This includes research into removing ultrafine particles and airborne pathogens.

- Energy Recovery Ventilation (ERV):

- R&D is aimed at improving the efficiency of ERV systems, which recover heat and moisture from exhaust air to pre-condition incoming fresh air.

- This helps to reduce the energy required for heating and cooling.

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD):

- CFD simulations are used to model airflow patterns in buildings and optimize the design of ventilation systems.

- This allows engineers to predict and improve the performance of ventilation systems before they are built.

- Indoor Air Quality Monitoring:

- Research is being conducted to develop more accurate and affordable indoor air quality monitoring devices.

- This allows building owners and occupants to track indoor air quality and take corrective action when necessary.

- Natural and Hybrid Ventilation:

- R&D explores how to optimize natural ventilation strategies, such as passive ventilation and stack ventilation.

- Hybrid systems that combine natural and mechanical ventilation are also being investigated.

- Impact of Airborne Pathogens:

- Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant increase in research on how ventilation systems can reduce the spread of airborne pathogens.

- This includes studies on the effectiveness of different ventilation strategies, such as increased ventilation rates and improved filtration.

Key Drivers of R&D:

- Energy efficiency:

- Reducing the energy consumption of buildings is a major driver of ventilation R&D.

- Indoor air quality:

- Growing awareness of the health impacts of poor indoor air quality is driving research into improved ventilation strategies.

- Sustainability:

- The desire to create sustainable buildings is driving the development of innovative ventilation technologies.

In summary, R&D in ventilation is focused on creating systems that provide healthy indoor air quality while minimizing energy consumption.

COURTESY : MEP Academy

References

- ^ Malone, Alanna. “The Windcatcher House”. Architectural Record: Building for Social Change. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012.

- ^ ASHRAE (2021). “Ventilation and Infiltration”. ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals. Peachtree Corners, GA: ASHRAE. ISBN 978-1-947192-90-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Whole-House Ventilation | Department of Energy

- ^ de Gids W.F., Jicha M., 2010. “Ventilation Information Paper 32: Hybrid Ventilation Archived 2015-11-17 at the Wayback Machine“, Air Infiltration and Ventilation Centre (AIVC), 2010

- ^ Schiavon, Stefano (2014). “Adventitious ventilation: a new definition for an old mode?”. Indoor Air. 24 (6): 557–558. Bibcode:2014InAir..24..557S. doi:10.1111/ina.12155. ISSN 1600-0668. PMID 25376521.

- ^ ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, ASHRAE, Inc., Atlanta, GA, US

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2024). “European residential ventilation: Investigating the impact on health and energy demand”. Energy and Buildings. 304. Bibcode:2024EneBu.30413839B. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113839.

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2022). “Outdoor PM2. 5 air filtration: optimising indoor air quality and energy”. Building & Cities. 3 (1): 186–203. doi:10.5334/bc.153.

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2024). “European residential ventilation: Investigating the impact on health and energy demand”. Energy and Buildings. 304. Bibcode:2024EneBu.30413839B. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113839.

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2023). “Influence of outdoor air pollution on European residential ventilative cooling potential”. Energy and Buildings. 289. Bibcode:2023EneBu.28913044B. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113044.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sun, Y., Zhang, Y., Bao, L., Fan, Z. and Sundell, J., 2011. Ventilation and dampness in dorms and their associations with allergy among college students in China: a case-control study. Indoor Air, 21(4), pp.277-283.

- ^ Kavanaugh, Steve. Infiltration and Ventilation In Residential Structures. February 2004

- ^ M.H. Sherman. “ASHRAE’s First Residential Ventilation Standard” (PDF). Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b ASHRAE Standard 62

- ^ How Natural Ventilation Works by Steven J. Hoff and Jay D. Harmon. Ames, IA: Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, Iowa State University, November 1994.

- ^ “Natural Ventilation – Whole Building Design Guide”. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012.

- ^ Shaqe, Erlet. Sustainable Architectural Design.

- ^ “Natural Ventilation for Infection Control in Health-Care Settings” (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO), 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Escombe, A. R.; Oeser, C. C.; Gilman, R. H.; et al. (2007). “Natural ventilation for the prevention of airborne contagion”. PLOS Med. 4 (68): e68. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040068. PMC 1808096. PMID 17326709.

- ^ Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) “Improving Ventilation In Buildings”. 11 February 2020.

- ^ Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) “Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities”. 22 July 2019.

- ^ Dr. Edward A. Nardell Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School “If We’re Going to Live With COVID-19, It’s Time to Clean Our Indoor Air Properly”. Time. February 2022.

- ^ “A Paradigm Shift to Combat Indoor Respiratory Infection – 21st century” (PDF). University ofGGBC Morawska, L, Allen, J, Bahnfleth, W et al. (36 more authors) (2021) A paradigm shift to combat indoor respiratory infection. Science, 372 (6543). pp. 689-691. ISSN 0036-8075

- ^ Video “Building Ventilation What Everyone Should Know”. YouTube. 17 June 2022.

- ^ Mudarri, David (January 2010). Public Health Consequences and Cost of Climate Change Impacts on Indoor Environments (PDF) (Report). The Indoor Environments Division, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. pp. 38–39, 63.

- ^ “Climate Change a Systems Perspective”. Cassbeth.

- ^ Raatschen W. (ed.), 1990: “Demand Controlled Ventilation Systems: State of the Art Review Archived 2014-05-08 at the Wayback Machine“, Swedish Council for Building Research, 1990

- ^ Mansson L.G., Svennberg S.A., Liddament M.W., 1997: “Technical Synthesis Report. A Summary of IEA Annex 18. Demand Controlled Ventilating Systems Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine“, UK, Air Infiltration and Ventilation Centre (AIVC), 1997

- ^ ASHRAE (2006). “Interpretation IC 62.1-2004-06 Of ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2004 Ventilation For Acceptable Indoor Air Quality” (PDF). American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ Fahlen P., Andersson H., Ruud S., 1992: “Demand Controlled Ventilation Systems: Sensor Tests Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine“, Swedish National Testing and Research Institute, Boras, 1992

- ^ Raatschen W., 1992: “Demand Controlled Ventilation Systems: Sensor Market Survey Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine“, Swedish Council for Building Research, 1992

- ^ Mansson L.G., Svennberg S.A., 1993: “Demand Controlled Ventilation Systems: Source Book Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine“, Swedish Council for Building Research, 1993

- ^ Lin X, Lau J & Grenville KY. (2012). “Evaluation of the Validity of the Assumptions Underlying CO2-Based Demand-Controlled Ventilation by a Literature review” (PDF). ASHRAE Transactions NY-14-007 (RP-1547). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ ASHRAE (2010). “ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 90.1-2010: Energy Standard for Buildings Except for Low-Rise Residential Buildings”. American Society of Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning Engineers, Atlanta, GA.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Ventilation. – 1926.57”. Osha.gov. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Air Infiltration and Ventilation Centre (AIVC). “What is smart ventilation?“, AIVC, 2018

- ^ “Home”. Wapa.gov. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ ASHRAE, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc, Atlanta, 2002.

- ^ “Stone Pages Archaeo News: Neolithic Vinca was a metallurgical culture”. www.stonepages.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Porter, Dale H. (1998). The Life and Times of Sir Goldsworthy Gurney: Gentleman scientist and inventor, 1793–1875. Associated University Presses, Inc. pp. 177–79. ISBN 0-934223-50-5.

- ^ “The Towers of Parliament”. www.parliament.UK. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ Alfred Barry (1867). “The life and works of Sir Charles Barry, R.A., F.R.S., &c. &c”. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Robert Bruegmann. “Central Heating and Ventilation: Origins and Effects on Architectural Design” (PDF).

- ^ Russell, Colin A; Hudson, John (2011). Early Railway Chemistry and Its Legacy. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84973-326-7. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Milne, Lynn. “McWilliam, James Ormiston”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17747. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Philip D. Curtin (1973). The image of Africa: British ideas and action, 1780–1850. Vol. 2. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-299-83026-7. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ “William Loney RN – Background”. Peter Davis. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Sturrock, Neil; Lawsdon-Smith, Peter (10 June 2009). “David Boswell Reid’s Ventilation of St. George’s Hall, Liverpool”. The Victorian Web. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1896). “Reid, David Boswell” . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 47. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Great Britain: Parliament: House of Lords: Science and Technology Committee (15 July 2005). Energy Efficiency: 2nd Report of Session 2005–06. The Stationery Office. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-10-400724-2. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Janssen, John (September 1999). “The History of Ventilation and Temperature Control” (PDF). ASHRAE Journal. American Society of Heating Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers, Atlanta, GA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Tredgold, T. 1836. “The Principles of Warming and Ventilation – Public Buildings”. London: M. Taylor

- ^ Billings, J.S. 1886. “The principles of ventilation and heating and their practical application 2d ed., with corrections” Archived copy. OL 22096429M.

- ^ “Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH): Carbon dioxide – NIOSH Publications and Products”. CDC. May 1994. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Lemberg WH, Brandt AD, and Morse, K. 1935. “A laboratory study of minimum ventilation requirements: ventilation box experiments”. ASHVE Transactions, V. 41

- ^ Yaglou CPE, Riley C, and Coggins DI. 1936. “Ventilation Requirements” ASHVE Transactions, v.32

- ^ Tiller, T.R. 1973. ASHRAE Transactions, v. 79

- ^ Berg-Munch B, Clausen P, Fanger PO. 1984. “Ventilation requirements for the control of body odor in spaces occupied by women”. Proceedings of the 3rd Int. Conference on Indoor Air Quality, Stockholm, Sweden, V5

- ^ Joshi, SM (2008). “The sick building syndrome”. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 12 (2): 61–64. doi:10.4103/0019-5278.43262. PMC 2796751. PMID 20040980. in section 3 “Inadequate ventilation”

- ^ “Standard 62.1-2004: Stricter or Not?” ASHRAE IAQ Applications, Spring 2006. “Archived copy” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014. accessed 11 June 2014

- ^ Apte, Michael G. Associations between indoor CO2 concentrations and sick building syndrome symptoms in U.S. office buildings: an analysis of the 1994–1996 BASE study data.” Indoor Air, Dec 2000: 246–58.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Stanke D. 2006. “Explaining Science Behind Standard 62.1-2004”. ASHRAE IAQ Applications, V7, Summer 2006. “Archived copy” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014. accessed 11 June 2014

- ^ Stanke, DA. 2007. “Standard 62.1-2004: Stricter or Not?” ASHRAE IAQ Applications, Spring 2006. “Archived copy” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014. accessed 11 June 2014

- ^ US EPA. Section 2: Factors Affecting Indoor Air Quality. “Archived copy” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ Belias, Evangelos; Licina, Dusan (2024). “European residential ventilation: Investigating the impact on health and energy demand”. Energy and Buildings. 304. Bibcode:2024EneBu.30413839B. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113839.