Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

The concept of “indoor ecological quality” is closely tied to “indoor environmental quality” (IEQ), and both have significant implications for human well-being and, by extension, prosperity. Here’s a breakdown:

Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ)

- Definition:

- IEQ encompasses the conditions inside a building that affect the health and comfort of its occupants.

- Key factors include:

- Air quality (pollutants, allergens, ventilation)

- Thermal comfort (temperature, humidity)

- Lighting (natural and artificial)

- Acoustics (noise levels)

- Ergonomics (workspace design)

- Impact on Prosperity:

- Health and Productivity:

- Poor IEQ can lead to health problems like respiratory issues, headaches, and fatigue, reducing productivity and increasing absenteeism.

- Conversely, good IEQ promotes well-being, leading to increased productivity and job satisfaction.

- Economic Benefits:

- Green buildings with high IEQ tend to have lower operating costs due to energy efficiency.

- Improved IEQ can increase property values and attract tenants.

- Sustainability:

- Focusing on IEQ encourages the use of sustainable building materials and practices, reducing environmental impact.

- Health and Productivity:

Connecting to “Ecological Quality”

- While IEQ focuses on the immediate indoor environment, “ecological quality” broadens the scope to include the impact of buildings on the wider ecosystem.

- Key connections:

- Sustainable Materials: Using building materials that are sustainably sourced and have low emissions.

- Energy Efficiency: Reducing energy consumption through efficient HVAC systems and natural lighting.

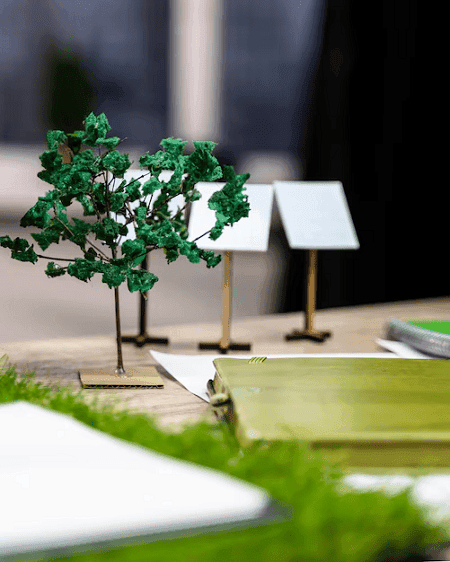

- Biophilic Design: Incorporating natural elements like plants and natural light to create a connection with nature.

- Ventilation: Ensuring that ventilation systems are filtering air properly, and that outside air being brought in is of a good quality.

- Prosperity and Ecological Quality:

- A focus on ecological quality leads to more sustainable and resilient buildings, which contribute to long-term economic and environmental prosperity.

- Healthy indoor environments contribute to a healthier population, which is essential for a thriving society.

In essence, prioritizing indoor ecological quality and IEQ is not just about comfort; it’s about creating healthy, productive, and sustainable spaces that contribute to individual and societal prosperity.

What is Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

The concept of “indoor ecological quality” builds upon the well-established idea of “indoor environmental quality” (IEQ) and extends it to include a stronger focus on the broader ecological impact. Here’s a breakdown:

Understanding the Components:

- Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ):

- This refers to the conditions within a building that influence the health and well-being of its occupants.

- Key factors include:

- Air quality (pollutants, allergens, ventilation)

- Thermal comfort (temperature, humidity)

- Lighting (natural and artificial)

- Acoustics (noise levels)

- Ergonomics (workspace design)

- Indoor Ecological Quality:

- This expands IEQ to consider the building’s impact on the wider ecosystem.

- It emphasizes:

- The use of sustainable and low-impact building materials.

- Energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions.

- The incorporation of biophilic design principles (connecting with nature).

- Minimizing the building’s overall ecological footprint.

The Link to Prosperity:

- Health and Productivity:

- High indoor ecological quality leads to healthier occupants, which translates to increased productivity in workplaces and improved learning in educational settings.

- Reduced health issues mean lower healthcare costs and fewer lost workdays.

- Economic Benefits:

- Green buildings with excellent IEQ and ecological quality often have lower operating costs due to energy efficiency.

- These buildings can also command higher property values and attract environmentally conscious tenants.

- Sustainability and Long-Term Prosperity:

- By prioritizing indoor ecological quality, we contribute to a more sustainable future, ensuring that resources are available for future generations.

- This approach promotes a healthier planet, which is essential for long-term economic and social prosperity.

- Enhanced well being:

- By bringing in elements of nature, and ensuring clean air, and comfortable environments, people have a greater sense of well being. This can lead to greater creativity, and better mental health.

In essence, “indoor ecological quality and prosperity” highlights the interconnectedness of human health, environmental sustainability, and economic well-being. By creating indoor environments that are both healthy for people and respectful of the planet, we can foster a more prosperous and sustainable future.

Who is required Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

Essentially, everyone benefits from improved indoor ecological quality and prosperity. However, certain groups and sectors have a particularly strong need and influence in this area:

- Building Occupants:

- This includes anyone who spends time indoors: residents, office workers, students, patients, etc. Their health, well-being, and productivity are directly affected by IEQ.

- Employers and Businesses:

- Businesses benefit from increased employee productivity, reduced absenteeism, and lower healthcare costs.

- They can also enhance their reputation and attract talent by providing healthy and sustainable workplaces.

- Building Owners and Managers:

- Landlords and property managers can increase property values and attract tenants by prioritizing IEQ.

- They can also reduce operating costs through energy efficiency.

- Schools and Educational Institutions:

- Students’ learning and performance are significantly impacted by indoor environmental conditions.

- Healthy school environments promote better attendance and academic outcomes.

- Healthcare Facilities:

- Hospitals and clinics require optimal IEQ to ensure patient recovery and prevent the spread of infections.

- Healthy indoor environments are crucial for patient well-being.

- Vulnerable Populations:

- Children, the elderly, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions are particularly susceptible to the negative effects of poor IEQ.

- Architects, Designers, and Construction Professionals:

- These professionals have a crucial role in designing and building healthy and sustainable indoor environments.

- Policy Makers and Governments:

- Governments can implement regulations and incentives to promote IEQ and sustainable building practices.

- They also have the responcibility to protect the public health.

In short, creating and maintaining high indoor ecological quality is a shared responsibility that benefits all of society.

When is required Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

The need for indoor ecological quality and prosperity is not a situational or temporary requirement; it’s an ongoing, pervasive need. Here’s a breakdown of when it’s essential:

Always, But With Increased Urgency In:

- New Construction and Renovations:

- This is the most crucial time to integrate IEQ and ecological considerations. Designing and building with sustainable materials, efficient systems, and biophilic principles from the outset is far more effective and cost-efficient than retrofitting.

- High-Occupancy Buildings:

- Schools, offices, hospitals, and public spaces where large numbers of people congregate require meticulous attention to IEQ to minimize health risks and maximize well-being.

- Urban Environments:

- Cities often suffer from air pollution and limited access to nature, making high-quality indoor environments even more critical for residents’ health.

- Climate Change Context:

- As climate change intensifies, the need for energy-efficient buildings with resilient designs becomes paramount. Reducing our carbon footprint and creating healthy indoor spaces are essential for mitigating climate impacts.

- Post-Pandemic Era:

- The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of indoor air quality and ventilation. Increased awareness has led to a greater demand for healthy indoor spaces.

- Vulnerable Populations:

- Where there are children, elderly people, or those with compromised health. These populations are more susceptible to the negative affects of poor IEQ. So it is always important to ensure their environments are of a high quality.

- Everyday Life:

- Because people spend such a large percentage of their lives indoors, it is always important to maintain a high level of indoor ecological quality.

In essence:

- The need is constant, but the urgency increases with factors like population density, environmental stress, and public health concerns.

By prioritizing IEQ and ecological quality in all building projects and maintenance efforts, we can create healthier, more sustainable, and more prosperous communities.

COURTESY : IIT Roorkee July 2018

Where is required Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

The need for indoor ecological quality and prosperity is widespread, but it’s particularly critical in these locations:

- Urban Environments:

- Cities often have high levels of air pollution and limited access to green spaces. Therefore, ensuring healthy indoor environments is essential for residents’ well-being.

- Residential Buildings:

- Homes are where people spend a significant amount of their time, so maintaining good IEQ is crucial for their health and comfort.

- Workplaces:

- Offices and other workspaces require high IEQ to promote employee productivity, reduce absenteeism, and minimize health risks.

- Educational Institutions:

- Schools and universities need healthy indoor environments to support students’ learning and development.

- Healthcare Facilities:

- Hospitals and clinics must prioritize IEQ to ensure patient recovery, prevent infections, and protect the health of staff.

- Public Buildings:

- Libraries, museums, and other public spaces should provide healthy and comfortable environments for visitors.

- Industrial Facilities:

- Factories and industrial plants must implement measures to control indoor air pollution and protect workers’ health.

- Any location where vulnerable populations reside:

- This includes nursing homes, childcare facilities, and any location where people with compromised health spend their time.

In essence, indoor ecological quality is essential in any enclosed space where people spend time.

How is required Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

Achieving indoor ecological quality and prosperity requires a multifaceted approach, integrating various strategies and technologies. Here’s a breakdown of key methods:

1. Ventilation and Air Quality:

- Improved Ventilation:

- Ensure adequate fresh air intake through natural ventilation (opening windows) or mechanical ventilation systems (HVAC).

- Implement heat recovery ventilators (HRVs) or energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) to minimize energy loss during ventilation.

- Air Filtration:

- Use high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters in HVAC systems to remove airborne pollutants.

- Consider air purifiers for specific areas.

- Source Control:

- Minimize indoor air pollution sources by using low-VOC (volatile organic compound) building materials, furniture, and cleaning products.

- Prohibit smoking indoors.

- Properly maintain and vent combustion appliances.

2. Thermal Comfort:

- Energy-Efficient HVAC Systems:

- Install high-efficiency heating and cooling systems.

- Implement zoning controls to regulate temperatures in different areas.

- Building Envelope Optimization:

- Improve insulation to minimize heat loss and gain.

- Use high-performance windows to reduce energy transfer.

- Implement smart window shading.

- Passive Design Strategies:

- Utilize natural ventilation and solar shading to regulate indoor temperatures.

3. Lighting:

- Natural Lighting:

- Maximize daylighting through strategically placed windows and skylights.

- Use light shelves and reflective surfaces to distribute natural light.

- Energy-Efficient Lighting:

- Use LED lighting to reduce energy consumption.

- Implement lighting controls, such as occupancy sensors and dimmers.

4. Acoustics:

- Noise Control:

- Use sound-absorbing materials to reduce noise levels.

- Design layouts to minimize noise transmission.

- Install good quality windows.

5. Biophilic Design:

- Incorporating Natural Elements:

- Introduce indoor plants to improve air quality and create a connection with nature.

- Use natural materials, such as wood and stone, in interior design.

- Provide views of nature.

6. Sustainable Materials:

- Eco-Friendly Building Materials:

- Use sustainably sourced and recycled materials.

- Choose materials with low environmental impact.

7. Monitoring and Management:

- Indoor Environmental Monitoring:

- Install sensors to monitor air quality, temperature, humidity, and lighting levels.

- Use building management systems to optimize IEQ.

- Regular Maintenance:

- Ensure regular cleaning and maintenance of HVAC systems and other equipment.

8. Policy and Education:

- Building Codes and Standards:

- Implement building codes and standards that promote IEQ and sustainability.

- Education and Awareness:

- Educate building occupants, designers, and contractors about the importance of IEQ.

By implementing these strategies, we can create indoor environments that are healthy, comfortable, and sustainable, fostering both ecological quality and prosperity.

Case study is Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

It’s important to understand that “Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity” is a broad concept, and case studies often focus on specific aspects of it. However, here’s how we can look at relevant case studies, and what they demonstrate:

Key Areas of Focus in Case Studies:

- Biophilic Design:

- Many studies examine how incorporating natural elements (plants, natural light, natural materials) into indoor spaces impacts occupant well-being and productivity.

- For example, studies on buildings with extensive green walls or atriums often show improvements in employee satisfaction and reduced stress levels.

- The case study provided from MDPI, regarding the Bell Museum, provides a very good look into how biophilic design effects people in a workplace.

- Green Building Certifications:

- Buildings that achieve certifications like GGBC DEMING RATING often serve as case studies for IEQ and sustainability.

- These certifications assess factors like air quality, energy efficiency, and material selection.

- Analyzing these buildings reveals how sustainable design practices can lead to healthier and more efficient indoor environments.

- Post-Occupancy Evaluations (POEs):

- POEs involve surveying building occupants to assess their satisfaction with the indoor environment.

- These studies provide valuable insights into how IEQ factors like temperature, lighting, and acoustics affect occupant comfort and productivity.

- The ANZAScA study regarding highrise mixed use buildings, is a great example of this.

- Impact of Indoor Plants:

- Numerous studies investigate the impact of indoor plants on air quality and occupant well-being.

- These studies often demonstrate that plants can remove certain pollutants from the air and improve psychological well-being.

What These Case Studies Demonstrate:

- Improved Health and Well-being:

- Case studies consistently show that improved IEQ leads to better health outcomes, reduced stress levels, and increased well-being.

- Increased Productivity:

- Healthy indoor environments contribute to increased productivity in workplaces and improved learning in educational settings.

- Energy Efficiency:

- Sustainable building practices and technologies can significantly reduce energy consumption and operating costs.

- The importance of monitoring:

- The need to monitor IEQ factors, to ensure that the building is performing as intended.

In essence, case studies in this area provide evidence that prioritizing indoor ecological quality is not just a theoretical concept, but a practical approach that yields tangible benefits for individuals and organizations.

COURTESY : Paul Cochrane

White paper on Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

It’s important to recognize that a single, definitive “white paper” titled exactly “Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity” might be less common than a collection of research and publications that address its various components. However, there’s a wealth of information available that covers the key aspects of this concept. Here’s a breakdown of where to find relevant information and the types of documents you’ll encounter:

Key Areas and Relevant Documents:

- Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) Research:

- Organizations like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) publish extensive research and guidelines on IEQ, covering topics like indoor air quality, ventilation, and thermal comfort.

- Academic journals and research databases contain numerous studies on the impact of IEQ on health, productivity, and well-being.

- Documents that analyze the economic benefits of IEQ improvements. These documents often have cost benefit analysis, that show the financial gains of improving IEQ.

- Green Building and Sustainable Design:

- Organizations like the GGBC GLOBAL GREEN BUILDING COUNCIL) provide resources and certifications (like GGBC) that promote sustainable building practices.

- These resources often include white papers and reports on topics like energy efficiency, sustainable materials, and biophilic design.

- Biophilic Design:

- Research on biophilic design explores the connection between humans and nature in the built environment.

- Publications from researchers and organizations focused on biophilia provide insights into the benefits of incorporating natural elements into indoor spaces.

- Health and Productivity Studies:

- Studies from organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and academic institutions examine the impact of indoor environments on human health and productivity.

- These studies often provide data and analysis that support the importance of IEQ.

Where to Find Information:

- Government Agencies:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- Non-Profit Organizations:

- GLOBAL GREEN BUILDING (GGBC )

- World Green Building Council (WGBC)

- Academic Databases:

- PubMed

- ScienceDirect

- ResearchGate

- Professional Organizations:

- ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers)

Key Themes in Relevant Documents:

- The link between IEQ and human health and well-being.

- The economic benefits of improved IEQ, including increased productivity and reduced healthcare costs.

- The importance of sustainable building practices and biophilic design.

- The role of technology in monitoring and improving IEQ.

While a single, all-encompassing white paper might be elusive, the information available from these sources provides a comprehensive understanding of the interconnectedness of indoor ecological quality and prosperity.

Industrial application of Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

The application of “Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity” within industrial settings is becoming increasingly important, driven by factors like worker well-being, sustainability regulations, and the desire for increased productivity. Here’s how these principles are being applied:

Key Industrial Applications:

- Manufacturing Facilities:

- Air Quality:

- Controlling industrial pollutants (dust, fumes, VOCs) through advanced filtration and ventilation systems.

- Implementing real-time air quality monitoring to ensure worker safety.

- Lighting:

- Optimizing natural and artificial lighting to reduce eye strain and improve worker visibility.

- Using energy-efficient LED lighting to lower operational costs.

- Thermal Comfort:

- Maintaining stable temperatures and humidity levels to enhance worker comfort and prevent heat stress.

- Designing facilities with proper insulation and ventilation to minimize energy consumption.

- Noise Control:

- Implementing noise reduction measures to protect workers from hearing damage.

- Creating quieter workspaces to improve communication and reduce stress.

- Air Quality:

- Warehouses and Logistics:

- Ventilation:

- Ensuring adequate ventilation to prevent the buildup of fumes from forklifts and other equipment.

- Maintaining proper air circulation to prevent mold and mildew growth.

- Lighting:

- Utilizing motion-sensor lighting to reduce energy consumption in large warehouse spaces.

- Maximizing natural daylighting to improve visibility and reduce reliance on artificial light.

- Ventilation:

- Laboratories and Cleanrooms:

- Air Filtration:

- Implementing HEPA filtration and other advanced air purification systems to maintain sterile environments.

- Monitoring air quality to ensure compliance with strict regulations.

- Environmental Control:

- Maintaining precise temperature, humidity, and pressure levels to ensure the integrity of experiments and products.

- Air Filtration:

- Offices within Industrial Complexes:

- The same needs of regular office spaces are needed, but with the added need of filtering and controlling the air quality, from the industrial processes happening within the same complex.

Benefits of Implementation:

- Improved Worker Health and Safety:

- Reduced exposure to pollutants and hazards.

- Lower rates of occupational illnesses.

- Increased Productivity:

- Healthier and more comfortable workers are more productive.

- Reduced absenteeism due to illness.

- Enhanced Sustainability:

- Reduced energy consumption and waste.

- Improved compliance with environmental regulations.

- Positive Company Image:

- Demonstrating a commitment to worker well-being and environmental responsibility.

By integrating these principles, industrial facilities can create healthier, more sustainable, and more productive work environments.

Research and development of Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity ?

The research and development (R&D) of “Indoor Ecological Quality and Prosperity” is a dynamic and evolving field, driven by increasing awareness of the interconnectedness between human health, environmental sustainability, and economic well-being. Here’s a look at key areas of R&D:

Key Research and Development Areas:

- Advanced Air Filtration and Purification:

- Development of new filtration materials and technologies that can remove a wider range of indoor pollutants, including ultrafine particles and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

- Research on smart air purification systems that can adapt to changing indoor conditions and optimize energy consumption.

- Biophilic Design and Human-Centered Environments:

- Studies on the psychological and physiological benefits of biophilic design elements, such as indoor plants, natural light, and natural materials.

- Development of new design strategies and technologies that can seamlessly integrate nature into indoor spaces.

- Research into how indoor environments effect mental health.

- Smart Building Technologies and Monitoring:

- Development of sensor networks and data analytics tools that can monitor indoor environmental conditions in real-time.

- Research on building automation systems that can optimize ventilation, lighting, and thermal comfort based on occupancy and environmental data.

- Development of user interfaces that provide building occupants with personalized feedback on their indoor environment.

- Sustainable Building Materials and Construction:

- Research on new materials that have low environmental impact and high durability.

- Development of innovative construction techniques that reduce waste and energy consumption.

- Studies into the full lifecycle of building materials, and their effects on indoor air quality.

- Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Integration:

- Development of high-efficiency HVAC systems and lighting technologies.

- Research on integrated renewable energy systems, such as solar panels and geothermal heat pumps.

- Research into passive building design, that uses natural elements to control indoor climates.

- Health and Well-being Studies:

- Epidemiological studies that examine the long-term health effects of indoor environmental exposures.

- Research on the impact of indoor environments on cognitive function, productivity, and mental health.

- Studies that investigate the effects of indoor environments on vulnerable populations, such as children and the elderly.

Key Drivers of R&D:

- Increasing awareness of the health impacts of poor IEQ.

- Growing demand for sustainable and energy-efficient buildings.

- Advances in sensor technology and data analytics.

- Government regulations and building codes that promote IEQ and sustainability.

- The need to create healthy and productive indoor environments in the post-pandemic era.

Organizations like the EPA, ASHRAE, and various universities and research institutions are actively involved in R&D related to indoor ecological quality and prosperity.

COURTESY : Soul Forest India

references

- ^ Van der Ryn S, Cowan S(1996). “Ecological Design”. Island Press, p.18

- ^ Martin Charter(2019). “Designing for the Circular Economy”. Abingdon, p.21

- ^ Anne-Marie Willis (1991), “An international Eco Design” conference

- ^ Iqbal, Muhammad Waqas; Kang, Yuncheol; Jeon, Hyun Woo (February 2020). “Zero waste strategy for green supply chain management with minimization of energy consumption”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 245: 118827. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118827.

- ^ Victor Papanek (1972), “Design for the Real World: Human Ecological and Social CHange”, Chicago: Academy Edition, p185.

- ^ Pataki, Diane E.; Santana, Carlos G.; Hinners, Sarah J.; Felson, Alexander J.; Engebretson, Jesse (2021). “Ethical considerations of urban ecological design and planning experiments”. Plants, People, Planet. 3 (6): 737–746. doi:10.1002/ppp3.10204. hdl:11343/275315. ISSN 2572-2611. S2CID 236267636.

- ^ Victor Papanek (1972), “Design for the Real World: Human Ecological and social change”, Chicago: Academy Edition, ix.

- ^ Papanek, Victor J. (1973). Design for the real world : human ecology and social change. New York, Pantheon Books. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-394-47036-8.

- ^ Victor Margolin (1997), “Design for a Sustainable World”, Design Issues, vol14, 2. pp. 85

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (Richard Buckminster) (1963). Nine chains to the moon. Carbondale, Southern Illinois Univ. Pr. pp. 252–259.

- ^ Dilnot, Clive (July 1982). “Design as a socially significant activity: An introduction”. Design Studies. 3 (3): 139–146. doi:10.1016/0142-694X(82)90006-0.

- ^ Margolin, Victor (1998). “Design for a Sustainable World”. Design Issues. 14 (2): 83–92. doi:10.2307/1511853. JSTOR 1511853.

- ^ Burns, Heather L. (2015). “Transformative sustainability pedagogy: Learning from ecological systems and indigenous wisdom”. Journal of Transformative Education. 13 (3): 259–276. doi:10.1177/1541344615584683. S2CID 146837158.

- ^ Robinson, Jake; Gellie, Nick; MacCarthy, Danielle; Mills, Jacob; O’Donnell, Kim; Redvers, Nicole (16 March 2021). “Traditional ecological knowledge in restoration ecology: a call to listen deeply, to engage with, and respect Indigenous voices”. Restoration Ecology. 29 (4). Bibcode:2021ResEc..2913381R. doi:10.1111/rec.13381. S2CID 233709809.

- ^ Gould, Kenneth A.; Lewis, Tammy L. (2017). Green Gentrification. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 115–150. ISBN 9781138920163.

- ^ Dooling, Sarah (2009). “Ecological gentrification: A research agenda exploring justice in the city”. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 33 (3): 621–639. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00860.x.

- ^ Wang, Lizhe; Bai, Jianbo; Wang, Hejin (February 2020). “The Research on Eco-design and Eco-efficiency of Life Cycle Analysis”. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 440 (4): 042042. Bibcode:2020E&ES..440d2042W. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/440/4/042042. ISSN 1755-1315. S2CID 216490866.

- ^ Aryampa, Shamim; Maheshwari, Basant; Sabiiti, Elly N; Zamorano, Montserrat (1 May 2021). “A framework for assessing the Ecological Sustainability of Waste Disposal Sites (EcoSWaD)”. Waste Management. 126: 11–20. Bibcode:2021WaMan.126…11A. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.044. PMID 33730655. S2CID 232299084.

- ^ Perkins, Tracy (2022). Evolution of a Movement: Four Decades of California Environmental Justice Activism. Oakland, California: University of California Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780520376984.

- ^ Perkins, Tracy (20 January 2021). “The multiple people of color origins of the US environmental justice movement: social movement spillover and regional racial projects in California”. Environmental Sociology. 7 (2): 147–159. Bibcode:2021EnvSo…7..147P. doi:10.1080/23251042.2020.1848502. S2CID 233312021.

- ^ Rasli, Amran; Qureshi, Muhammad Imran; Isah-Chikaji, Aliyu; Zaman, Khalid; Ahmad, Mehboob (January 2018). “New toxics, race to the bottom and revised environmental Kuznets curve: The case of local and global pollutants”. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 81: 3120–3130. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.092. S2CID 158417495.

- ^ Wheeler, Stephen M. (October 2012). “Urban Ecological Design: A Process for Regenerative Places by Danilo Palazzo and Frederick Steiner”. Journal of Regional Science. 52 (4): 719–720. Bibcode:2012JRegS..52..719W. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.2012.00784_10.x.

- ^ Demos, T.J. (2009). “The Politics of Sustainability: Art and Ecology”. Radical Nature: 17–27.

- ^ Godway, Eleanor M. (2011). “Art as the Truth of Tomorrow: Expression and the Healing of the World”. International Journal of the Arts in Society. 5: 33–40.

- ^ Taieb, Amine Hadj; Hammami, Manel; Msahli, Slah; Sakli, Faouzi (October 2010). “Sensitising Children to Ecological Issues through Textile Eco-Design”. International Journal of Art & Design Education. 29 (3): 313–320. doi:10.1111/j.1476-8070.2010.01648.x. ISSN 1476-8062.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lewis, Tania (April 2008). “Transforming citizens? Green politics and ethical consumption on lifestyle television”. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies. 22 (2): 227–240. doi:10.1080/10304310701864394. S2CID 144299069.

- ^ Schäfer, M.; Löwer, M. (31 December 2020). “Ecodesign—A Review of Reviews”. Sustainability. 13 (1): 315. doi:10.3390/su13010315.

- ^ Baumann, H.; Boons, F.; Bragd, A. (October 2002). “Mapping the green product development field: engineering, policy and business perspectives”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 10 (5): 409–425. doi:10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00015-X. S2CID 154313068. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. (November 2016). “Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions”. Design Studies. 47: 118–163. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2016.09.002. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Pigosso, D.C.; McAloone, T.C.; Rozenfeld, H. (2015). “Characterization of the State-of-the-art and Identification of Main Trends for Ecodesign Tools and Methods: Classifying Three Decades of Research and Implementation” (PDF). Journal of the Indian Institute of Science. 94 (4): 405–427. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Rossi, M.; Germani, M.; Zamagni, A. (15 August 2016). “Review of ecodesign methods and tools. Barriers and strategies for an effective implementation in industrial companies”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 129: 361–373. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.051. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Thomé, A.M.T.; Scavarda, A.; Ceryno, P.S.; Remmen, A. (2016). “Sustainable new product development: A longitudinal review”. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy. 18 (7): 2195–2208. Bibcode:2016CTEP…18.2195T. doi:10.1

- McLennan, J. F. (2004), The Philosophy of Sustainable Design

- ^ “Environmental Sustainable Design (ESD) | the City of Greater Bendigo”. www.bendigo.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- ^ The End of Unsustainable Design, Jax Wechsler, December 17, 2014.

- ^ JA Tainter 1988 The Collapse of Complex Societies Cambridge Univ. Press ISBN 978-0521386739

- ^ Buzz Holling 1973 Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems

- ^ Acaroglu, L. (2014). Making change: Explorations into enacting a disruptive pro-sustainability design practice. [Doctoral dissertation, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology].

- ^ Waste and recycling, DEFRA

- ^ Household waste, Office for National Statistics.

- ^ US EPA, “Expocast“

- ^ Victor Papanek (1972), “Design for the Real World: Human Ecological and Social Change”, Chicago: Academy Edition, p87.

- ^ Kulibert, G., ed. (September 1993). Guiding Principles of Sustainable Design – Waste Prevention. United States Department of the Interior. p. 85. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Anastas, Paul T.; Zimmerman, Julie B. (2003). “Peer Reviewed: Design Through the 12 Principles of Green Engineering”. Environmental Science & Technology. 37 (5): 94A – 101A. Bibcode:2003EnST…37…94A. doi:10.1021/es032373g. PMID 12666905.

- ^ Anastas, P. L., and Zimmerman, J. B. (2003). “Through the 12 principles of green engineering”. Environmental Science and Technology. March 1. 95-101A Anastas, P. L., and Zimmerman, J. B. (2003).

- ^ Anastas, P. L., and Zimmerman, J. B. (2003). “Through the 12 principles of green engineering”. Environmental Science and Technology. March 1. 95-101A Anastas, P. L., and Zimmerman, J. B. (2003). “Through the 12 principles of green engineering”. Environmental Science and Technology. March 1. 95-101A

- ^ D. Vallero and C. Brasier (2008), Sustainable Design: The Science of Sustainability and Green Engineering. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, ISBN 0470130628.

- ^ US DOE 20 yr Global Product & Energy Study Archived 2007-06-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Paul Hawken, Amory B. Lovins, and L. Hunter Lovins (1999). Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-35316-8

- ^ Ryan, Chris (2006). “Dematerializing Consumption through Service Substitution is a Design Challenge”. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 4(1). doi:10.1162/108819800569230

- ^ Kulibert, G., ed. (September 1993). Guiding Principles of Sustainable Design – The Principles of Sustainability. United States Department of the Interior. p. 4. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ The End of Unsustainable Design Jax Wechsler, December 17, 2014. The End of Unsustainable Design, Jax Wechsler, December 17, 2014.

- ^ Examples

- ^ “Vegan Interior Design by Deborah DiMare”. VeganDesign.Org – Sustainable Interior Designer. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ “The Ecothis.eu campaign website”. ecothis.eu. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ Chapman, J., ‘Design for [Emotional] Durability’, Design Issues, vol xxv, Issue 4, Autumn, pp29-35, 2009 doi:10.1162/desi.2009.25.4.29

- ^ Page, Tom (2014). “Product attachment and replacement: implications for sustainable design” (PDF). International Journal of Sustainable Design. 2 (3): 265. doi:10.1504/IJSDES.2014.065057. S2CID 15900390. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Chapman, J., Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy, Earthscan, London, 2005

- ^ Page, Tom (2014). “Product attachment and replacement: implications for sustainable design” (PDF). International Journal of Sustainable Design. 2 (3): 265. doi:10.1504/IJSDES.2014.065057. S2CID 15900390. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Lacey, E. (2009). Contemporary ceramic design for meaningful interaction and emotional durability: A case study. International Journal of Design, 3(2), 87-92

- ^ Clark, H. & Brody, D., Design Studies: A Reader, Berg, New York, US, 2009, p531 ISBN 9781847882363, Bloomberg Businessweek, April 07, 2010]

- ^ “Interview with Peter Eisenman”. Intercontinental Curatorial Project. October 2003. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Kriston Capps, “Green Building Blues,” The American Prospect, February 12, 2009

- ^ Claire Easley (7 August 2012). “Not Pretty? Then It’s Not Green”. Builder.

- ^ “Not built to last | Andrew Hunt”. The Critic Magazine. 2021-10-15. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- ^ “Unified Architectural Theory: Chapter 10”. ArchDaily. 2015-04-26. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- ^ Green Design: What’s Love Got to Do with It? Building Green By Paula Melton, December 2, 2013 Green Design: What’s Love Got to Do with It? Building Green, By Paula Melton, December 2, 2013

- ^ Kenton, W. (2021, March 04). Greenwashing. Retrieved from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/greenwashing.asp

- ^ Sherman, Lauren, “Eco-Labeling: An Argument for Regulation and Reform” (2012). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 49. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/49

- ^ Du, Qian & Nguyen, Quynh. (2010). Effectiveness of Eco-label? : A Study of Swedish University Students’ Choice on Ecological Food.

- ^ Birkeland, J. (2020). Net-positive design and sustainable urban development. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-25855-9.

- ^ Fan Shu-Yang, Bill Freedman, and Raymond Cote (2004). “Principles and practice of ecological design Archived 2004-08-14 at the Wayback Machine“. Environmental Reviews. 12: 97–112.

- ^ Meinhold, Bridgette (2013). Urgent Architecture: 40 Sustainable Housing Solutions for a Changing World. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 9780393733587. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Vidal, John (2013-05-07). “Humanitarian intent: Urgent Architecture from ecohomes to shelters – in pictures”. The Guardian. theguardian.com. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ “URGENT ARCHITECTURE: Inhabitat Interviews Author Bridgette Meinhold About Her New Book”. YouTube.com. 7 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Escobar Cisternas, Melissa; Faucheu, Jenny; Troussier, Nadege; Laforest, Valerie (December 2024). “Implementing strong sustainability in a design process”. Cleaner Environmental Systems. 15: 100224. doi:10.1016/j.cesys.2024.100224.

- ^ Ji Yan and Plainiotis Stellios (2006): Design for Sustainability. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press. ISBN 7-112-08390-7

- ^ Enas Alkhateeba; Bassam Abu Hijlehb (2017). “Potential of upgrading federal buildings in the United Arab Emirates to reduce energy demand” (PDF). International High-Performance Built Environment Conference – A Sustainable Built Environment Conference 2016 Series (SBE16), iHBE 2016. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Holm, Ivar (2006). Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial design: How attitudes, orientations, and underlying assumptions shape the built environment. Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 82-547-0174-1.

- ^ “Rolf Disch – SolarArchitektur”. more-elements.com.

- ^ Kent, Michael; Parkinson, Thomas; Kim, Jungsoo; Schiavon, Stefano (2021). “A data-driven analysis of occupant workspace dissatisfaction”. Building and Environment. 205: 108270. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108270.

- ^ ASHRAE Guideline 10-2011: “Interactions Affecting the Achievement of Acceptable Indoor Environments“

- ^ “Charter of the New Urbanism”. cnu.org. 2015-04-20.

- ^ “Beauty, Humanism, Continuity between Past and Future”. Traditional Architecture Group. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Issue Brief: Smart-Growth: Building Livable Communities. American Institute of Architects. Retrieved on 2014-03-23.

- ^ “Driehaus Prize”. Together, the $200,000 Driehaus Prize and the $50,000 Reed Award represent the most significant recognition for classicism in the contemporary built environment. Notre Dame School of Architecture. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Beatley, Timothy (2011). Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning. Washington, DC: Timothy Beatley Springer e-books. ISBN 978-1-59726-986-5.

- ^ Kellert, Stephen R.; Heerwagen, Judith; Mador, Martin, eds. (2008). Biophilic design: the theory, science, and practice of bringing buildings to life. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-16334-4. OCLC 140108292.

- ^ Arvay, Clemens G. (2018). The biophilia effect: a scientific and spiritual exploration of the healing bond between humans and nature. Boulder, Colorado: Sounds True. ISBN 978-1-68364-043-1.

- ^ Mollison, B.; Holmgren, D. (1981). Perma-Culture. 1: A perennial agriculture for human settlements. Winters, Calif: Tagari. ISBN 978-0-938240-00-6.

- ^ Bane, Peter (2013). The Permaculture handbook. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86571-666-7.

- ^ Mollison, Bill (2004). Permaculture: a designers’ manual. Tagari. ISBN 978-0-908228-01-0.

- ^ Benyus, Janine M. (2009). Biomimicry: innovation inspired by nature (Nachdr. ed.). New York, NY: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-053322-9.

- ^ Pawlyn, Michael (2016). Biomimicry in architecture. Riba publishing. ISBN 978-1-85946-628-5.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (1991). Dwellers in the land: the bioregional vision. New Society Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86571-225-6.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (2000). Dwellers in the land: the bioregional vision. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2205-6.

- ^ MacGinnis, Michael Vincent, ed. (2006). Bioregionalism. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15445-1.

- ^ Thayer, Robert L., ed. (2003). LifePlace: bioregional thought and practice. Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23628-8.

- ^ Lyle, John Tillman (1994). Regenerative design for sustainable development. Wiley series in sustainable design. New York, NY: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-17843-9.

- ^ Van der Ryn, Sim; Cowan, Stuart (2007). Ecological design. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-59726-140-1. OCLC 78791353.

- ^ Wahl, Daniel Christian (2022). Designing regenerative cultures. Triarchy Press. ISBN 978-1-909470-77-4.

- ^ McDonough, William; Braungart, Michael (2002). Cradle to cradle: remaking the way we make things. North Point Press. ISBN 978-0-86547-587-8.

- ^ Webster, Ken; Blériot, Jocelyn; Johnson, Craig; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, eds. (2013). Effective business in a circular economy. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9927784-1-5.

- ^ Lacy, Peter; Rutqvist, Jakob (2015). Waste to wealth: the circular economy advantage. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-53068-4.

- ^ Pérez, Gabriel; Perini, Katia, eds. (2018). Nature based strategies for urban and building sustainability. Oxford Cambridge: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-812150-4.

- ^ Kabisch, Nadja; Korn, Horst; Stadler, Jutta; Bonn, Aletta, eds. (2017). Nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation in urban areas: linkages between science, policy and practice. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-53750-4.

- ^ Hawken, Paul, ed. (2017). Drawdown: the most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-313044-4.

- ^ Reeder, Linda (2016). Net zero energy buildings: case studies and lessons learned. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-138-78123-8.

- ^ Hootman, Thomas (2013). Net zero energy design: a guide for commercial architecture. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-01854-5.

- ^ Johnston, David; Gibson, Scott (2010). Toward a zero energy home: a complete guide to energy self-sufficiency at home. ISBN 978-1-60085-143-8.

- ^ “Nature Positive Guidelines for the Transition in Cities” (PDF).

- ^ Birkeland, Janis (2022). “Nature Positive: Interrogating Sustainable Design Frameworks for Their Potential to Deliver Eco-Positive Outcomes”. Urban Science. 6 (2): 35. doi:10.3390/urbansci6020035. ISSN 2413-8851.

- ^ Fukuoka, Masanobu; Metreaud, Frederic P. (1985). The natural way of farming: the theory and practice of green philosophy. ISBN 978-81-85987-00-2.

- ^ Birkeland, Janis (2007). “Positive Development: Designing for Net-positive Impacts”.

- ^ Birkeland, Janis (2008). Positive development: from vicious circles to virtuous cycles through built environment design. Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-579-9.

- ^ Birkeland, Janis (2020). Net-positive design and sustainable urban development. New York London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-367-25856-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The CSI sustainable design and construction practice guide by Construction Specifications Institute – PDF Drive”. www.pdfdrive.com. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ The Difference Between Green and Sustainable by Mercedes Martty The Difference Between Green and Sustainable by Mercedes Martty

- ^ “Sustainable Interior Designer”. ECO Canada. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Sustainable Design”. www.gsa.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “EPA”. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Center, Illinois Sustainable Technology. “LibGuides: Sustainable Product Design: Sustainable Design Principles”. guides.library.illinois.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ Kent, Michael; Jakubiec, Alstan (2021). “An examination of range effects when evaluating discomfort due to glare in Singaporean buildings”. Lighting Research and Technology. 54 (6): 514–528. doi:10.1177/14771535211047220. S2CID 245530135. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ “Sustainable Interior Designer”. ECO Canada. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Sustainable Interior Design | Green Hotelier”. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “The Commercial Interior Design Association”. www.iida.org. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Sustainability”. www.iida.org. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Athena Sustainable Materials Institute”. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Knowledge Base”. BuildingGreen. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ US EPA, OA (2013-02-22). “Summary of the Energy Policy Act”. US EPA. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007”. www.govinfo.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Executive Order — Planning for Federal Sustainability in the Next Decade”. whitehouse.gov. 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Guiding Principles for Sustainable Federal Buildings”. Energy.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ US EPA, OCSPP (2013-08-09). “Safer Choice”. US EPA. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Proximity Hotel | Greensboro, North Carolina”. Proximity Hotel. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Shanghai Natural History Museum – Home”.

- ^ “Awards & Accolades”. Vancouver Convention Centre. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “World’s “greenest commercial building” awarded highest sustainability mark”. newatlas.com. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ WA, DEI Creative in Seattle. “Bullitt Center”. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ “Sustainable Sydney 2030 – City of Sydney”. www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ What Is Sustainable Urban Planning?What Is Sustainable Urban Planning?

- ^ “Renewable Energy Policy Project & CREST Center for Renewable Energy and Sustainable Technology”

- ^ Koli, Pooran; Sharma, Urvashi; Gangotri, K.M. (2012). “Solar energy conversion and storage: Rhodamine B – Fructose photogalvanic cell”. Renewable Energy. 37: 250–258. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2011.06.022.

- ^ Kulibert, G., ed. (September 1993). Guiding Principles of Sustainable Design – Energy Management. United States Department of the Interior. p. 69. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ “Water recycling & alternative water sources”. health.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010.

- ^ US EPA, OP (2015-07-30). “Sustainable Manufacturing”. www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ “Sustainable Roadmap – Open Innovation”. connect.innovateuk.org. 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ What is Sustainable Technology? Perceptions, Paradoxes, and Possibilities (Book)

- ^ J. Marjolijn C. Knot; Jan C.M. van den Ende; Philip J. Vergragt (June 2001). “Flexibility strategies for sustainable technology development”. Technovation. 21 (6): 335–343. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(00)00049-3. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Florian Popescu, How to bridge the gap between design and development Florian Popescu, How to bridge the gap between design and development

- ^ “World IP Day 2020: Design rights and sustainability”. www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2022-09-19